- India

- International

Line of Actual Control (LAC): Where it is located, and where India and China differ

India-China Line of Actual Control: As tensions continue between India and China along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), a look at what the line means on the ground and the disagreements over it.

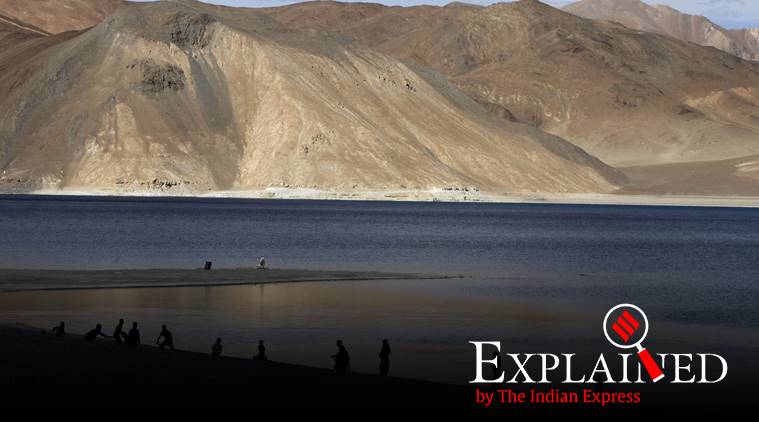

People stand by the banks of the Pangong Lake, near the India-China border in Ladakh, India. (AP Photo: Channi Anand, File)

People stand by the banks of the Pangong Lake, near the India-China border in Ladakh, India. (AP Photo: Channi Anand, File)

As tensions continue between India and China along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), a look at what the line means on the ground and the disagreements over it:

What is the Line of Actual Control?

The LAC is the demarcation that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory. India considers the LAC to be 3,488 km long, while the Chinese consider it to be only around 2,000 km. It is divided into three sectors: the eastern sector which spans Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, the middle sector in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, and the western sector in Ladakh.

What is the disagreement?

The alignment of the LAC in the eastern sector is along the 1914 McMahon Line, and there are minor disputes about the positions on the ground as per the principle of the high Himalayan watershed. This pertains to India’s international boundary as well, but for certain areas such as Longju and Asaphila. The line in the middle sector is the least controversial but for the precise alignment to be followed in the Barahoti plains.

The major disagreements are in the western sector where the LAC emerged from two letters written by Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai to PM Jawaharlal Nehru in 1959, after he had first mentioned such a ‘line’ in 1956. In his letter, Zhou said the LAC consisted of “the so-called McMahon Line in the east and the line up to which each side exercises actual control in the west”. Shivshankar Menon has explained in his book Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy that the LAC was “described only in general terms on maps not to scale” by the Chinese.

After the 1962 War, the Chinese claimed they had withdrawn to 20 km behind the LAC of November 1959. Zhou clarified the LAC again after the war in another letter to Nehru: “To put it concretely, in the eastern sector it coincides in the main with the so-called McMahon Line, and in the western and middle sectors it coincides in the main with the traditional customary line which has consistently been pointed out by China”. During the Doklam crisis in 2017, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson urged India to abide by the “1959 LAC”.

Indian soldiers near the Line of Actual Control at Chushul, 59 kilometers from Pangong lake in Leh. (Express Photo: Shuaib Masoodi)

Indian soldiers near the Line of Actual Control at Chushul, 59 kilometers from Pangong lake in Leh. (Express Photo: Shuaib Masoodi)

What was India’s response to China’s designation of the LAC?

India rejected the concept of LAC in both 1959 and 1962. Even during the war, Nehru was unequivocal: “There is no sense or meaning in the Chinese offer to withdraw twenty kilometres from what they call ‘line of actual control’. What is this ‘line of control’? Is this the line they have created by aggression since the beginning of September?”

India’s objection, as described by Menon, was that the Chinese line “was a disconnected series of points on a map that could be joined up in many ways; the line should omit gains from aggression in 1962 and therefore should be based on the actual position on September 8, 1962 before the Chinese attack; and the vagueness of the Chinese definition left it open for China to continue its creeping attempt to change facts on the ground by military force”.

When did India accept the LAC?

Shyam Saran has disclosed in his book How India Sees the World that the LAC was discussed during Chinese Premier Li Peng’s 1991 visit to India, where PM P V Narasimha Rao and Li reached an understanding to maintain peace and tranquillity at the LAC. India formally accepted the concept of the LAC when Rao paid a return visit to Beijing in 1993 and the two sides signed the Agreement to Maintain Peace and Tranquillity at the LAC. The reference to the LAC was unqualified to make it clear that it was not referring to the LAC of 1959 or 1962 but to the LAC at the time when the agreement was signed. To reconcile the differences about some areas, the two countries agreed that the Joint Working Group on the border issue would take up the task of clarifying the alignment of the LAC.

Why did India change its stance on the Line of Actual Control?

As per Menon, it was needed because Indian and Chinese patrols were coming in more frequent contact during the mid-1980s, after the government formed a China Study Group in 1976 which revised the patrolling limits, rules of engagement and pattern of Indian presence along the border.

In the backdrop of the Sumdorongchu standoff, when PM Rajiv Gandhi visited Beijing in 1988, Menon notes that the two sides agreed to negotiate a border settlement, and pending that, they would maintain peace and tranquillity along the border.

Have India and China exchanged their maps of the LAC?

Only for the middle sector. Maps were “shared” for the western sector but never formally exchanged, and the process of clarifying the LAC has effectively stalled since 2002. As an aside, there is no publicly available map depicting India’s version of the LAC.

During his visit to China in May 2015, PM Narendra Modi’s proposal to clarify the LAC was rejected by the Chinese. Deputy Director General of the Asian Affairs at the Foreign Ministry, Huang Xilian later told Indian journalists that “We tried to clarify some years ago but it encountered some difficulties, which led to even complex situation. That is why whatever we do we should make it more conducive to peace and tranquillity for making things easier and not to make them complicated.”

Is the LAC also the claim line for both countries?

Not for India. India’s claim line is the line seen in the official boundary marked on the maps as released by the Survey of India, including both Aksai Chin and Gilgit-Baltistan. In China’s case, it corresponds mostly to its claim line, but in the eastern sector, it claims entire Arunachal Pradesh as South Tibet. However, the claim lines come into question when a discussion on the final international boundaries takes place, and not when the conversation is about a working border, say the LAC.

An Army convoy moves along a Srinagar-Leh highway leading to Ladakh, at Gagingir in Ganderbal district. (Express Photo: Shuaib Masoodi)

An Army convoy moves along a Srinagar-Leh highway leading to Ladakh, at Gagingir in Ganderbal district. (Express Photo: Shuaib Masoodi)

But why are these claim lines controversial in Ladakh?

Independent India was transferred the treaties from the British, and while the Shimla Agreement on the McMahon Line was signed by British India, Aksai Chin in Ladakh province of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir was not part of British India, although it was a part of the British Empire. Thus, the eastern boundary was well defined in 1914 but in the west in Ladakh, it was not.

A G Noorani writes in India-China Boundary Problem 1846-1947 that Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel’s Ministry of States published two White Papers on Indian states. The first, in July 1948, had two maps: one had no boundary shown in the western sector, only a partial colour wash; the second one extended the colour wash in yellow to the entire state of J&K, but mentioned “boundary undefined”. The second White Paper was published in February 1950 after India became a Republic, where the map again had boundaries which were undefined.

In July 1954, Nehru issued a directive that “all our old maps dealing with this frontier should be carefully examined and, where necessary, withdrawn. New maps should be printed showing our Northern and North Eastern frontier without any reference to any ‘line’. The new maps should also be sent to our embassies abroad and should be introduced to the public generally and be used in our schools, colleges, etc”. This map, as is officially used till date, formed the basis of dealings with China, eventually leading to the 1962 War.

How is the LAC different from the Line of Control with Pakistan?

The LoC emerged from the 1948 ceasefire line negotiated by the UN after the Kashmir War. It was designated as the LoC in 1972, following the Shimla Agreement between the two countries. It is delineated on a map signed by DGMOs of both armies and has the international sanctity of a legal agreement. The LAC, in contrast, is only a concept – it is not agreed upon by the two countries, neither delineated on a map or demarcated on the ground.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05