- India

- International

From Hashomer to NILI, the history of Israeli intelligence, its successes and failures

Israel's intelligence community is one of the best funded, most connected, and highly effective operators internationally. It's foreign intelligence, Mossad, is particularly lauded for a series of successful operations conducted during the 20th century. However, after the October 2023 attack by Hamas, the reputation of Israeli intelligence has taken a significant hit.

Israeli intelligence has come under criticism for failing to anticipate the attack from Hamas

Israeli intelligence has come under criticism for failing to anticipate the attack from Hamas Israeli media reports suggest that Shin Bet, the country’s internal security service along with the Mossad, tasked with foreign intelligence, have set up a special unit to track down the Hamas members who organised the deadly October 7 attack that killed more than 1,500 Israelis.

The name chosen for the task force is supposedly NILI — a Hebrew acronym for the Biblical phrase meaning ‘The Eternal One of Israel will not lie’. The unit takes on a symbolic value as well, sharing its name with the NILI espionage network which assisted the British in its fight against the Ottoman Empire in Palestine during the First World War.

Ahron Bregman, an Israeli political scientist at King’s College London who spent six years in the Israeli army tells France24, NILI’s operations are likely to resemble those of the Mossad during Operation Wrath of God, in which the agency tracked down the terrorists involved in the Munich Olympics massacre, killing them methodically over the span of 20 years.

Operations like Wrath of God contribute to the almost mythical reputation that Israel’s intelligence agencies, and in particular, the Mossad, have developed since 1948. However, while those agencies have overseen a number of successful operations, they have also been held responsible for some of the country’s most devastating intelligence failures.

Pre-1948

Israel’s intelligence capabilities can be traced all the way back to 1909, long before the official formation of the Israeli state. Hashomer, or the Watchmen, was a group founded by some of the earliest Israeli immigrants into Palestine. An unofficial unit, it was tasked with blending into the local communities and collecting information on potential attacks. Over its 10 years of existence, Hashomer had at most 100 members but its modus operandi — of adopting local customs in order to remain overlooked — was the basis of the current intelligence community.

Some members of Hashomer were recruited by the British during World War I, and organised into a network known as NILI. Operational between 1915 and 1917, NILI counted around 30 members but despite its diminutive size, was rendered greatly effective due to British training. Erez David Maisel, in an interview with Spycast, a YouTube podcast, explains why the formation of the NILI was so seminal. Maisel, who formerly served as Brigadier General and Director of the Israel Defense Forces, states, “the most important thing about the World War I experience is that there suddenly is intelligence capability, although its nascent. It’s very new, it’s very small, it’s very secret but it has some success.”

Group portrait of members of Hashomer

Group portrait of members of Hashomer

From 1920 onwards, the Hashomer and NILI were replaced by the Haganah, founded to defend Jewish presence in British Palestine. According to Maisel, the Haganah established intelligence services on a national level but their activities were relatively moderate until 1940, in accordance with the Jewish community policy of self-restraint. However by the end of the Second World War, that restraint was to diminish dramatically.

During WWI, the Jews fought for both sides, although mostly allied with the British. That changed in the 1930s with the rise of fascism in Europe, and particularly in Germany and Italy that were home to a considerable Jewish population. Jews now started fleeing Europe for Palestine in large numbers (what’s known as the Yeshu) and brought with them crucial knowledge. These migrants would form a key portion of Haganah’s intelligence operations, using methods adopted from Europe, and relying on both overt and clandestine support from the British.

The big question thereafter was how to protect the existing Jewish settlements and the incoming immigrants in a country that was technically under British mandate but where the British had little control, and there was an Arab population that was opposed to Jewish settlement.

Formation of the IDF

Soon after Israel became independent, the government recognised the need to establish a durable intelligence structure, especially militarily. In June 1948, the first prime minister of the State, David Ben-Gurion, decided to create three intelligence organisations under the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) — Aman (military intelligence), Shin Bet, and eventually Mossad. Ben-Gurion knew early on that Israel would be met with serious hostility, and made the decision to bolster the country’s security and intelligence capabilities significantly. Aman’s mandate was to collect intelligence on Arab states’ militaries and protect Israeli internal security. Shin Bet was tasked with domestic intelligence and counterespionage, while Mossad was the central authority for collecting foreign intelligence, including covert relations with other states and special operations.

Israel’s intelligence community was successful during the first Arab-Israeli War but according to Maisel, it was only in 1956 that it garnered international attention. In 1956, during the heart of the Cold War, Premier of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev delivered a powerful speech in Moscow, in which he denounced his predecessor, Joseph Stalin, for his humanitarian offenses. Although the speech was supposed to be top secret, the Mossad and Shabat in Warsaw were able to get their hands on the document when a Jewish man in Moscow used his charms to access the transcript. They were able to get it to Tel Aviv and hand it over to Israeli intelligence, making the CIA realise that Mossad had access behind the Iron Curtain. Thereafter, Mossad and the CIA, and by extension Israel and the United States, would embark on an intelligence partnership that remains strong till today.

The relationship has reaped dividends for all involved. For Washington, as the Jewish Virtual Library notes, Israel is the only state in the Middle East upon whom it can rely on for intelligence. Towards this end, Israel has assisted America in a number of espionage operations including identifying Soviet missile systems during the Cold War, intercepting Iran’s nuclear programme in 2010 and providing Washington with a list of Westerners that had joined ISIS in 2014.

In turn, the CIA has provided Mossad with training and expertise, intelligence sharing and technology, particularly in the realm of counter-terrorism. Due to necessity, partnerships and good organisation, the Mossad has developed a reputation for success, bolstered by a number of key interventions it conducted in the 20th century.

Successes

Throughout its history, Mossad and Shin Bet have captured, and sometimes assassinated, individuals abroad deemed dangerous to the state of Israel. One of the most famous operations they conducted was the capture in Argentina of the Nazi fugitive Adolf Eichmann in 1960.

After World War II, Eichmann managed to flee Germany and lived under an assumed identity in various countries. Although a number of Nazi hunters, including Simon Wiesenthal, dedicated themselves to finding Eichmann and other Nazis, it was under the most unpredictable circumstances that he was finally identified. In 1956, a Jewish German living in Argentina named Lothar Hermann heard from his daughter that her boyfriend routinely boasted about his father’s Nazi exploits during the war.

Hermann instructed his daughter to confirm the accuracy of these claims, and upon receiving a sufficient answer, altered a German prosecutor named Fritz Bauer, to Eichmann’s presence in Bueno Aires. Bauer, not trusting the German authorities, turned to Israel instead, who sent a team of Shin Bet agents to identify and interrogate Eichmann. In May 1960, a team of Mossad operatives, led by Peter Malkin, executed a covert operation, capturing Eichmann as he disembarked a bus near his residence. The capture was a well-planned manoeuvre, carried out without the knowledge of Argentine authorities. Eichmann was clandestinely transported to Israel, disguised as an airline worker before being put to trial in Jerusalem.

When Ben-Gurion announced to the Israeli parliament that Eichmann had been captured, he was met with disbelief. “How, in what way, where?” asked his transport minister. Ben-Gurion deflected the query, stating simply, “that is why we have a security service.”

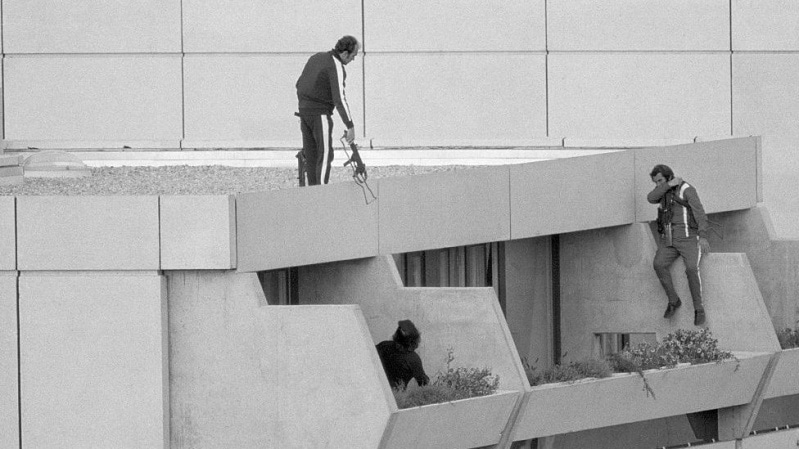

Another key operation led by the Mossad was the search and assassination of members of the Black September terrorist group that had murdered 11 Israeli athletes during the 1972 Munich Olympic games and assassinated Jordanian Prime Minister Wasfi Tal. Although Israel had previously targeted the leaders of groups like Fatah, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), these assassinations by Israel became much more common after the Munich massacre. According to reports, a covert Israeli committee led by Defence Minister Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister Golda Meir approved the execution of everyone connected to Black September, the Fatah-affiliated organisation, either directly or indirectly.

Members of the Black September Group storm the Olympic Village in Munich (Wikimedia Commons)

Members of the Black September Group storm the Olympic Village in Munich (Wikimedia Commons)

The Wrath of God hit squad, also known as Bayonet, was backed by IDF special operations units and consisted of agents from Mossad. In the aftermath of the tragedy, Mossad initiated a relentless 20 year pursuit that spanned the corners of the globe.

In October 1972, the hit squad shot and assassinated Wael Zwaiter, a PLO organiser and the cousin of President of the Palestinian National Authority Yasser Arafat, in the lobby of his Rome apartment building. The next target was Mahmoud Hamshari, the PLO representative in Paris. The following months saw the deaths of four more suspects, but the most dramatic mission of the operation was to occur in 1973, spearheaded by Ehud Barak, who would go on to become Prime Minister of Israel.

The mission, known as Operation Spring of Youth, entailed bringing amphibious commando units into Beirut, in Lebanon. After coming ashore, they diverted attention by dressing as civilians and coordinated their actions with Mossad agents who were already present in the city. Three suspected terrorists were killed when a group of Israeli paratroopers attacked the PFLP headquarters, while other commando teams carried out deceptive raids around the city.

Describing the operation, Barak said that, due to his “baby face” he was designated as one of the disguised women. “I was a brunette,” he recounts, “with lipstick and blue on the eye,” and military socks stuffed into his breasts. Upon returning home, his wife began to question him as to why there was makeup smeared across his face. “I couldn’t tell her,” he states, but luckily for him, she discovered the truth when she heard a radio broadcast narrating the events. While the operation successfully eliminated several individuals linked to the Munich attack, it also led to controversy and international scrutiny due to the extrajudicial nature of the measures taken.

In Lillehammer, Norway, in 1973, the squad inadvertently murdered an innocent man after misidentifying one of its targets. Five Mossad agents were apprehended and found guilty as a result of the Norwegian authorities’ investigation into the crime, which also dismantled the organisation’s vast network of agents and safehouses across Europe. Furthermore, while Mossad killed several prominent Palestinians during the operation, they never managed to kill the mastermind behind the Munich massacre, Abu Daoud.

Along with the successes however, came a number of high-profile failures, the most prominent being the 1973 attacks against Israel that led to the Yom Kippur War or the 1973 Arab-Israeli War.

Previous intelligence failures

The seeds of the Yom Kippur War were planted by the Rotem Crisis, a confrontation between Israel and the United Arab Republic in February 1960. Israel was caught off guard when Egypt unleashed its armed troops on its mostly undefended southern front, spurred by tensions near the Israeli–Syrian border. The crisis had an impact on the events that preceded the 1967 Six-Day War even though hostilities did not break out.

In a 1996 article titled Rotem, published in Sage Journals, the Israeli political scientist Uri Bar-Joseph, discusses why Rotem occurred, explaining that Israeli intelligence forces were falsely lulled by their success in the 1956 war with Egypt. Believing that Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser would not risk instigating war with Israel, Aman failed to respond to information suggesting that Egypt was preparing to mobilise its army.

It was only after an American tip off, that Israel deployed its military forces to its borders with Egypt. By then Egyptian forces had deployed both close to the border and in depth, and Israel’s forces in the Negev, consisting of between 20 and 30 tanks, were now facing 500 Egyptian tanks and SU-100 tank destroyers. During the ensuing crisis, IDF Chief of Operations Yitzhak Rabin sent the commander in chief of the Israeli intelligence services, a note saying, “we’ve been caught with our pants down. During the next twenty four hours everything depends on the air force.”

The Israel Defense Forces General Staff subsequently issued a series of instructions, codenamed Rotem, for an emergency transfer of soldiers but, recognising its strategic disadvantage soon shifted its focus to the diplomatic front. It emphasised in overtures to the US and the UN both the growing military presence of Arab forces on its borders and the falsity of Arab intelligence about its alleged military plans against Syria.

Within a month, both sets of forces began to withdraw, although from an Egyptian perspective, the operation was a massive success. An editorial in Egypt daily Al-Ahram described the crisis as an Egyptian deployment reacting to a potential Israeli invasion of Syria, prompting the Israeli cabinet to act diplomatically rather than militarily. The Egyptian media described the outcome as a brilliant victory for their army.

The Rotem Crisis was the most significant test to Israel’s deterrence theory in the years between the Suez Crisis and the Six-Day War, with Maisel arguing that it “changed the priorities of the intelligence community”. However, by the time Israel concluded the Six-Day War in 1967, with a stunning victory, its intelligence community seemingly forgot the lessons of Rotem.

On October 6, 1973, on Yom Kippur (the day of atonement), one of the holiest days in the Jewish calendar, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise military assault against Israel. During the years preceding the conflict, the IDF depended on its intelligence apparatus to offer early warning of a military assault by Egypt and Syria. However, without such prior notice on Yom Kippur, the Israeli leadership was taken off guard as the IDF failed to call in its reserve forces in time to effectively repel the Arab invasion.

Israel was caught off guard with thousands of its troops and commanders injured in the ensuing conflict, 2,600 of whom lost their lives. Israel paid a heavy price in this war for the conceit fostered by its quick military triumph over Syria and Egypt just six years earlier. Ultimately, the Egyptian and Syrian forces were defeated by Israel (with significant assistance from the US) within 19 days. However, the Yom Kippur War was viewed by the Arabs as a triumph. The Israeli force had been caught off guard by Egypt and Syria, who also managed to advance on the Golan Heights and reach the Suez Canal, leading many Israelis to believe that Israel was defeated.

On the 50 year anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, Israel was attacked once again by Hamas. The date, according to most observers, is no coincidence. Like they were in 1973, the Israeli intelligence services were caught with their pants down.

How bad was the recent intelligence failure?

The events of October 7 have been described as the worst terrorist attack ever to have occurred on Israeli soil. While policy makers will share part of the blame, it will be the intelligence community that shoulders much of the responsibility. According to Laura Blumenfeld, an analyst of Middle East studies at John Hopkins University, who spoke to indianexpress.com, the scale of the intelligence failure is near unprecedented, and will have serious consequences for senior leadership. “The Israeli intelligence community is a reflective group,” she says, “they will accept responsibility for what happened and will adapt accordingly.”

Colin Clarke, the director of research at the Soufan Group, an intelligence and security consultancy, says the Hamas attack would have required years of preparation, signalling a huge oversight from both human and electronic intelligence. “I’m still astonished that a breakdown in intelligence occurred at this level,” Clarke told the BBC. “I don’t think anybody, including the Israelis, were prepared for an operation this complex and multi-pronged.”

According to senior Hamas leadership, the planning for the attack was long in the making. Ali Barakeh, a member of Hamas’ exiled leadership in Lebanon, said senior members intentionally projected a “rational” image to the world to hide its intentions. To help keep it from Israeli intelligence, only “a limited number of Hamas leaders knew it” was coming, Barakeh told Russia TV.

However, even he and his fellow Hamas leaders couldn’t predict the scale of their deadly attack. “We were surprised by this great collapse,” Barakeh separately told the Associated Press. Another anonymous diplomatic source told the Middle Eastern news outlet Al-Monitor that the plan had been significantly more modest. “Their success surprised them, too.”

Although Israeli intelligence agencies have admitted blame, their initial response, or lack thereof, could be chalked up to a number of factors according to Blumenfeld, including being stretched thin on Israel’s northern border, being distracted by domestic Israeli politics, believing that Hamas was focused on governance, and failing to identify their use of stone age technology during the planning stages. Jake Williams, a former US National Security Agency hacker, alludes to another point as well. “Intelligence in an environment like Israel isn’t finding a needle in a haystack—it’s finding the needle that will hurt you in a pile of needles,” Williams told the Council on Foreign Relations.

The truth probably lies somewhat in the middle – there was an intelligence failure, but not solely an intelligence failure. Either way, the attacks have affected the reputation of agencies like Mossad and Shin Bet.

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05