- India

- International

When Napoleon wanted to conquer India

Napoleon Bonaparte's fascination with the Orient, especially India, spurred his ambition to challenge Britain's hold on the subcontinent. Despite forming diplomatic treaties with the likes of Persia and Russia, Napoleon faced significant challenges in his quest to conquer India.

Napoleon's forces marching towards India

Napoleon's forces marching towards India For the ambitious Napoleon Bonaparte, the Orient had been a source of fascination from a very young age. He had read a great deal about the region and was fueled by admiration for the Macedonian emperor Alexander’s conquests in Asia. His real interest in India though emerged around 1798 when he carried out the expedition to Egypt. He wanted to threaten the French empire’s foremost enemy, Britain, and disrupt the emerging British trade with India.

Shortly before he left for Egypt, he is known to have told his Directoire that “as soon as he became master of Egypt, he would establish relations with the Indian princes, and, together with them, attack the British in their possessions.” In particular, he was keen on joining the forces of Tipu Sultan and helping him drive the British out of India.

It is to be noted that the French by this time already had a commercial presence in India in the form of the French East India Company’s colonies in Pondicherry, Mahe, Chandannagar, Karaikal and Yanon. Further, from the mid of the 1700s, the French East India Company began allying with the princely states who sought their assistance in succession disputes or external attacks. French mercenaries were employed by the Mughal emperors as well as the regional rulers such as those in Hyderabad, Bhopal, Punjab and in the army of Tipu Sultan of Mysore. Consequently, as noted by historian Barbara Ramusack in her book The Indian Princes and their States (2004), events in Europe and throughout the world impacted the social and political landscape of India significantly. “For example, the advent of Napoleon stimulated French interest in India and his defeat increased the number of unemployed French mercenaries seeking employment in India,” she writes.

Although in Egypt Napoleon was faced with a crushing defeat by Britain and Tipu Sultan died soon after in 1799, the French emperor’s ambitions of taking over British India were far from being stalled. The many plans and strategies devised by Napoleon to take over India are contextualised in the background of the dynamic territorial struggles being played out among the numerous colonial powers in Europe of the time, particularly the British, Russians and the French.

The Russian offer

Soon after his defeat in Egypt though, Napoleon was approached by the Russian Tsar Paul I. This was the time of the Great Game, a period of strategic rivalry between Britain and Russia in their attempt to claim territory across much of Asia. In 1801, the Tsar sent a secret proposition to Napoleon to carry out a joint invasion of India and drive out the English and the East India Company once and for all. The territory would then be divided between the two powers.

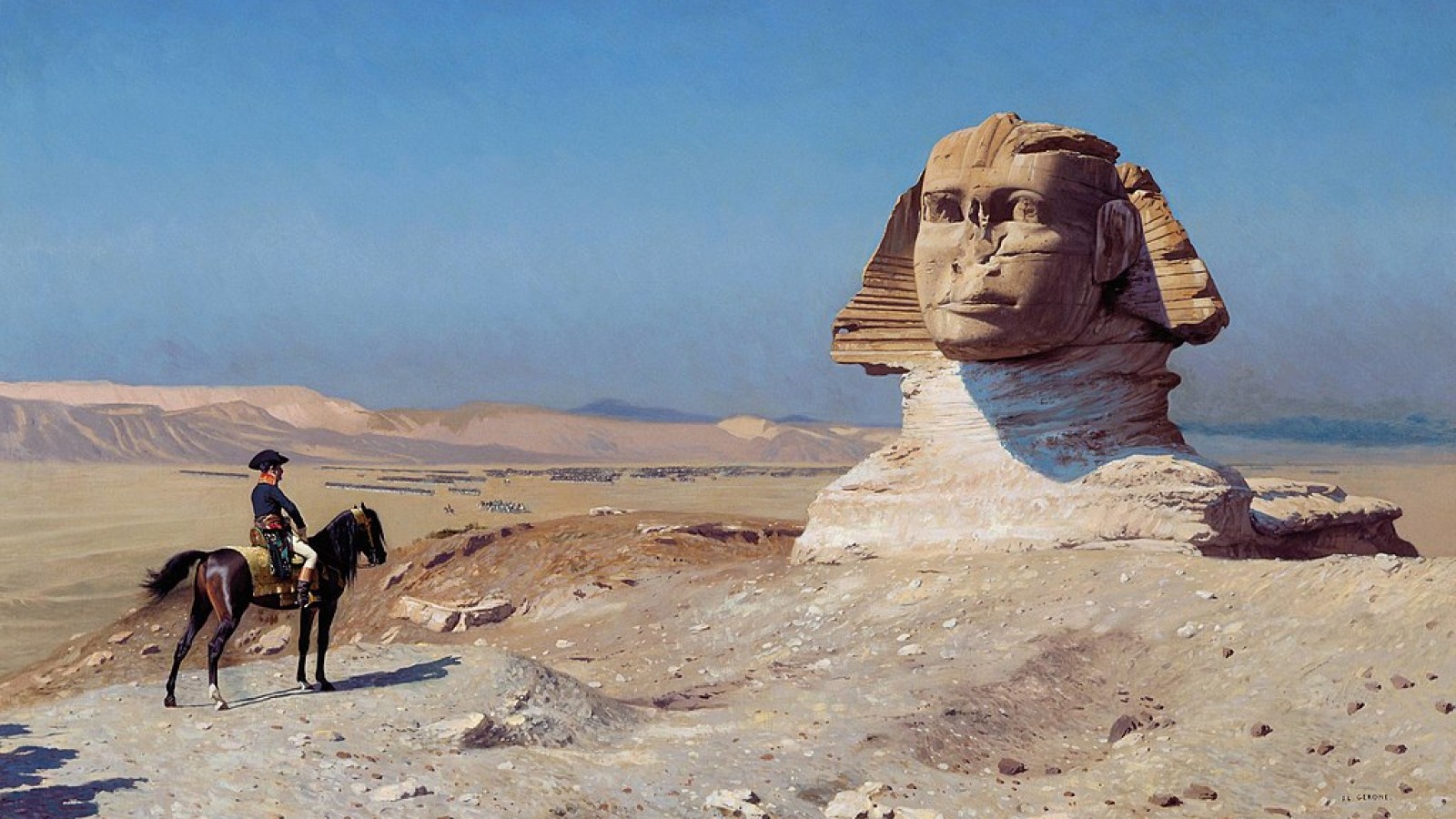

Napoleon Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (Oil on Canvas painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme/Wikimedia Commons)

Napoleon Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (Oil on Canvas painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme/Wikimedia Commons)As described by author Riaz Dean in his book Mapping The Great Game: Explorers, Spies & Maps in Nineteenth-century Asia (2020), “the Tsar believed a Cossack force of 35,000 together with a similar-sized French army would be amble for victory- perhaps with some help from the fierce Turcoman tribes who may be induced to join their expedition along the way.” The plan was that the Russians would meet with the French south of the Caspian Sea and then enter India through Persia and Afghanistan. All of this, the Tsar estimated, would take about four months.

The young Napoleon was apprehensive of the Tsar’s suggestion and refused to join hands with him. Despite not getting any French support and being discouraged by his own officials, the Tsar decided to continue on his own. But the expedition was aborted just about a month later when news broke of the Tsar being assassinated.

Meanwhile, Napoleon started courting yet another probable accomplice in his ambitions for the Orient. This was Persia, which would soon find itself embroiled in a bitter territorial conflict between the three imperial powers — the French, the Russians and the British.

The role played by Persia

Sitting strategically between Europe and the Indian subcontinent, the critical importance of Persia was not lost upon any of the imperial powers. For Napoleon, Persia was to serve the best possible means for his access to India. By 1800 itself, French agents were rumoured to have been courting the Shah of Persia, Fath Ali. Historian Amita Das in her book Defending British India against Napoleon (2016) notes that during the early 1800s French spies and agents infiltrated into Persia, “at first in various disguises and later through diplomatic channels.”

On realising that the French threat from Persia was looming large, the British soon decided to send in their own envoys to bond with the Shah. Captain John Malcolm, a handsome young man who had stayed at the court of the Nizam in Hyderabad and spoke Persian fluently, was the best bet for the British. In January 1801, Malcolm concluded both a commercial and a political treaty with Persia. The latter specified that “should it ever happen that an army of the French nation attempts to settle on any of the islands or shores of Persia, a conjunct force shall be appointed by the two high contracting parties, to act in cooperation, to destroy it.” The treaty also sought assurance from the Persians that they would go to war against the Afghans should they decide to move against India.

The British were caught between supporting Russia or France (Generated using AI)

The British were caught between supporting Russia or France (Generated using AI)

The treaty had conveniently left out the Russians. Napoleon had by then crowned himself emperor of France and was threatening all of Europe. Given the situation, the British did not wish to alienate the Russians. And yet it was the Russians who were the biggest threat to Persia.

A year later, Russia annexed the small independent kingdom of Georgia which the Persians considered to be under their dominance. By 1804, the Russians kept advancing further and took over the city of Erivan in present-day Armenia. Perturbed by the continuous acts of aggression by the Russians, the Shah reached out to Britain for assistance in accordance with the treaty of 1801. The British immediately shied away citing the fact that the treaty made no mention of Russia.

Consequently, Fath Ali had no other option but to turn to France for help. In the winter of 1804, while still battling the Russians at the gates of Erivan, he wrote a letter to Napoleon. By the spring of 1805, Napoleon sent two unofficial envoys to Persia to test waters there. But it was only in 1807 that he got into an official treaty with Persia.

Through the Treaty of Finkenstein, France guaranteed to Persia its territorial integrity. Iradj Amini in his book Napoleon and Persia (1999) writes that the treaty also “acknowledged her legitimate rights to Georgia, from which, and from all other Persian territory, France would make every effort to drive Russia.” France also promised to provide Russia with military assistance and help organise her artillery and infantry along European lines. In return, Persia agreed to immediately declare war on Britain and suspend all political and commercial ties with her.

Meanwhile, France was also engaged in the Napoleonic wars with Russia. Just about two months after France got into a treaty with Persia, while negotiating peace with Russia in the Battle of Friedland, Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I signed the Treaty of Tilsit. Dean in his book notes that during the peace talks the French emperor “discussed his grand design of combining their forces to conquer and divide the world between them- the West going to France and the East to Russia.”

“Through the treaty, Napoleon was mainly seeking to secure the supremacy of Europe, even if he had to give the Russians a free rein on the Asian continent,” writes Amini.

Napoleon also suggested to the Tsar that together they would march through Turkey to India with the support of Persia. Alexander I agreed to the plan and is known to have commented, “I hate the English as much as you do and am ready to assist you in any undertaking against them.”

This secret treaty between France and Russia was sure to be of much inconvenience to the Persians who had joined hands with the French only in the hope of keeping the Russians away. News of the Treaty of Tilsit reached the British through a spy, which reports suggest could have been a disaffected Russian nobleman who secretly listened in on the meeting between the two emperors.

Once the Shah was informed about this secret deal, he had no other option but to turn back to the British for assistance. Once again a new treaty was signed. The British were aware of the Shah’s fascination for large diamonds and is known to have gifted him one costing R.11000 that perhaps convinced the monarch to forget the past disagreements. Under the terms of the new treaty between the British and the Persians, the latter was to not allow a foreign army to pass across their country to India.

On the other hand, Britain promised aid to Persia in case she came under attack by a foreign power even if the invader happened to be on friendly terms with the British. The Shah, this time, was careful in ensuring an extra clause specifying British support in case of threat from Russia. This apart, the Persian ruler also ensured that he be paid a large amount annually along with British assistance to modernise his army.

This new treaty put an end to Napoleon’s long-cherished dream of taking over India.

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05