- India

- International

How the idea of Indian Union Territories was conceived and executed

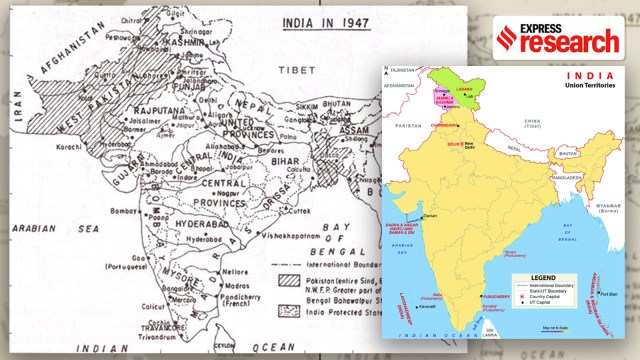

Although the original list of Union Territories mostly contained areas which were considered ‘backward’ or tribal, it went on to be altered significantly to include places like Chandigarh as well as the French and Portuguese colonies.More recently, Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh were added to the list. Adrija Roychowdhury and Srijana Siri find out how the idea of Union Territories was conceived in India and how they evolved.

The concept of Union Territory was introduced in the report of the States Reorganisation Commission in 1955.

The concept of Union Territory was introduced in the report of the States Reorganisation Commission in 1955. By 1948-49, the language issue had become a burning factor in the popular sentiment of Independent India. The Kannada speakers across the states of Madras, Mysore, Bombay and Hyderabad who had been demanding a separate administrative unit since the late 20th century renewed their movement, the Marathi and Malayalam speakers both desired respective political units of their own, while a separate Mahagujarat movement had started too. But it was the movement for the creation of the state of Andhra in the early 1950s which was the final spark. It convinced Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru that the division of India along linguistic lines was not only inevitable but also a matter of great urgency.

Soon after the creation of Andhra Pradesh on October 1, 1953, Nehru is known to have written to a colleague, “You will observe, that we have disturbed a hornet’s nest and I believe most of us are likely to be badly stung” (as cited by Ramachandra Guha in India After Gandhi). Much against his will, Nehru appointed a States Reorganisation Commission (SRC) to make recommendations to resolve the linguistic problem in India. Comprising Justice Fazil Ali, KM Panikkar and HN Kunzru, the Commission travelled across 104 towns and cities between 1954 and 1955, interviewed more than 9,000 people, and received as many as 152,250 written submissions.

The Commission submitted its report in September, 1955, recommending the reorganisation of India’s administrative units to form 14 states on linguistic lines and six centrally administered territories. This was the first time that the term Union Territory (UT) was used. The original six UTs consisted of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Laccadive, Minicoy and Amindivi islands (later renamed as Lakshadweep), Delhi, Manipur, Tripura, and Himachal Pradesh.

The character and evolution of Union Territories in India is intriguing given that there is very little homogeneity across these tiny enclaves spread across the country, other than the fact that they all come under the administration of the Centre. Although the original list of such regions mostly contained areas which were considered ‘backward’ or tribal, it went on to be altered significantly to include places like Chandigarh as well as the French and Portuguese colonies.

More recently, in October 2019, Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh became separate Union Territories. As noted by senior advocate Fali S. Nariman in an op-ed piece, “Not only was the area of the state of Jammu and Kashmir substantially diminished, its status too was unilaterally altered from state to union territory- a situation neither warranted nor justified by any provision in the Constitution.”

Indian states during the British Rule

At the time of Independence, only 60 per cent of modern-day India was under British occupation. The remaining 40 per cent belonged to the 565 Princely states.

Author Venkataraghavan Srinivasan in the book The Origin Story of India’s States, writes that the then deputy prime minister Vallabhai Patel and secretary of state VP Menon “visited every ruler and secured their signatures on the Standstill Agreement and the Instrument of Accession in record time”.

The state boundaries of most princely states were retained and absorbed into the Union of India in its entirety. The State Reorganisation Commission was deeply cognizant of this fact and investigated the history of territorial boundaries of the Indian states in the 1950s.

The Commission reported that the “existing structure of the States of the Indian Union” is due to the “growth of the British power in India and the historic process of the integration of former Indian States”. It noted that this provincial organisation of British India was designed to serve a dual purpose. First, “to uphold the direct authority of the supreme power in areas of vital economic and strategic importance” such as Bengal and Bombay. Second, “to fill the political vacuum arising from the destruction or collapse of the former rulers”. The Commission also noted that the British were aware of the artificial and convenient division of the provinces.

The structuring of the provinces in British India took place throughout the 19th century as the British expanded their territories. For instance, the coastal Presidencies of Madras and Bombay acquired their final shape in 1801 and 1827, respectively. The Central Provinces were formed only in 1861. As a result, the formation of states was grounded in imperial interests rather than any welfare or pleas of the masses.

By the early 20th century, nationalism began to influence territorial changes in provinces. With the ongoing reform movement in Bengal, sentiments of nationalism and desire for freedom also arose. To curtail any further development of these sentiments, in 1905, Bengal was divided into two parts — East Bengal and Assam and the rest of Bengal, which included the western part of Bengal and modern-day Bihar, Orissa and Chota Nagpur Plateau.

Lord Curzon, the then Governor-General of India, cited reasons emerging out of peculiar linguistic and racial conditions of the province. Although the Partition of Bengal was annulled later, Assam was constituted in 1912 and a separate province of Bihar and Orissa was also formed.

Indian states after Independence

In the early years after Independence, the territorial boundaries of the states remained consistent with British India. The administrative structure of the provinces was also similar.

Under the British, there existed three forms of provincial governments — the rule of a governor and Executive council, administration by a Lieutenant Governor, and those administered by a Chief Commissioner. A distinction was also made between the territories that were administered directly by the central government and the provinces that had their administrative structures. Territories that were administered by the Chief Commissioner fell directly under the rule of the central government.

In the Constitution of Independent India, this division is reflected as Part A, B, andC. Part A states consisted of the erstwhile Governor states such as Bombay, and Madras. Part B, which had an elected legislature, included states like Mysore and Saurashtra. Part C states like Delhi and Himachal Pradesh were controlled by the Chief Commissioner. Later, Part D states were introduced as territories that were administered by the central government, with no provision for a local legislature. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands alone were included under this category.

Political scientist Sudhir Kumar, in the book Political and Administrative Setup of Union Territories in India, mentions that Part C and Part D states were later converted to Union Territories with direct administration from the central government. During British rule, most of these states were recognised as Scheduled Districts under the Scheduled Districts Act, 1874. The provision of this Act was to apply no general laws to these territories. The areas included under the Act — Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Minicoy — were considered to be backward and underdeveloped and were administered by a Chief Commissioner.

In 1911, when Delhi was made the capital of India, it was converted to a Chief Commissioner’s Province. The Government of India Act, 1935 introduced that the Chief Commissioner’s provinces should be directly administered by the Centre.

During the drafting of the new Constitution in July 1947, the Constituent Assembly set up a committee to assess and report on the suitable constitutional changes in the administrative system of Chief Commissioners provinces. The Committee argued that provinces like Coorg and Delhi should be administered by the Lieutenant Governor and an elected legislature. However, in areas like Andaman and Nicobar Islands, direct control of the central government was preferred.

These suggestions were included in the Draft Constitution of India in 1948. The areas would be administered by the President through the Chief Commissioner or the Lieutenant Governor. The Draft Constitution also provided authority for the President to create a local legislature if needed.

However, these provisions were severely criticised when the Constitution Drafting Committee presented them in the Constituent Assembly in November 1948.

Political Scientist, Sudesh Kumar Sharma in his book, Union Territory Administration in India, mentions that Mukut Behari Lal, member of the Constituent Assembly from Ajmer, believed that the provision of a central administration “would only prevent the establishment of a responsible government”.

Sharma writes that there were three major grounds on which the provisions were criticised. First, the areas have no right to exist as separate units; they can be merged with other neighbouring states. Second, the administration in these areas would be expensive and take a toll on the financial health of the state. Last, the scheme is undemocratic such that most of the administration will depend on the President’s will and not the people.

Despite criticism, the Drafting Committee chose to include these provisions in the Constitution and adopted a list of centrally administered states, which included Ajmer, Bhopal, Coorg, Manipur, Kutch, Tripura, Bilaspur, Delhi and Himachal Pradesh.

Consequently, the Parliament passed the Government of the Part ‘C’ States Act in 1951 by which legislatures and Council of Ministers were created. All Part C states did not enjoy a uniform pattern of internal order. Some like Delhi and Coorg had an elected legislature, while others like Manipur only had advisory councils. Andaman and Nicobar Islands, on the other hand, did not have a local legislature or an advisory council and were controlled entirely by the President through a Chief Commissioner.

The birth of Union Territories

Historian Ramachandra Guha in India After Gandhi writes that during the freedom movement itself, the Congress party endorsed a linguistic-based division of states on multiple occasions. However, after Independence, Nehru felt the development of a national spirit was crucial as the country was still trying to heal the wounds of Partition. Nehru argued in favour of keeping intact the existing administrative units.

However, the massive unrest in Madras for the creation of a separate state of Andhra forced Nehru to change his thoughts on the matter. Further, the SRC report recognised that the states constituting the Union of India were unequal in resources, population and size. Importantly, they are also unequal before the law.

The Commission believed that the Indian Union must only have states with an “equal status and uniform relationship with the Centre, except for any strategic, security or other compelling reason”. They considered Part A as the standard of equality and freedom every state must possess. Consequently, they proposed abolishing Part B and Part C states.

While the abolishing of Part B states would not pose any problem given that they have sufficient resources and infrastructure for good governance, Part C states presented a wide range of problems.

As a category, all Part C states were far away from each other and were multi-linguistic and multicultural, unlike their neighbouring states.

Constitutionally, they did not follow a uniform administrative structure. Given that the Part C states proposed linguistic and cultural affinity with their neighbouring states a merger was not out of the question. However, for that to happen, these regions would have to undergo radical economic and political transformation to be at par with the Part A states.

The Commission insisted on an individual analysis of each state and proposed that while a merger is ideal, it is only fair to the people who were placed under the Centre for specific purposes like economic development to continue to benefit from that arrangement. Therefore, central authority in states like Himachal Pradesh, Kutch and Tripura that needed economic upliftment would continue.

The report also referred to other countries with a federal structure that faced a similar issue. “Countries with a federal constitution do contain some centrally-administered areas besides constituent units of the federation. These are, firstly the seats of federal governments such as Washington DC in the USA and Canberra in Australia, and secondly other administered territories consisting mostly of sparsely-populated and geographically isolated areas,” it suggested.

Consequently, it proposed that the administrative units of the Indian Union be classified into two categories — States and Territories.

The states would form the primary constituents of India and have a federal relationship with the Centre. The territories, on the other hand, cannot be part of any of the states and are centrally administered. The territories would be represented in the Union legislature but there would be no division of responsibilities. Democracy in the territories would be more participative and people would be encouraged to associate with the administration. If any of these territories wish for a fully democratic form of government, they must merge with another state.

By The Constitution (Seventh Amendment) Act, 1956, the territories were declared to be Union Territories. Himachal Pradesh and Tripura also joined the list of Union Territories along with Delhi, Manipur, and the Andaman and Nicobar islands.

In the years to come, the original list of Union Territories would undergo several changes. To begin with, Himachal Pradesh, Tripura, and Manipur attained full statehood by the 1970s. Chandigarh, which was caught in a custody battle between Punjab and Haryana, was made into a capital for both and put under the administration of the central government as a Union Territory in September 1966.

The French and Portuguese enclaves in India which were liberated a few years after British India, were mostly categorised as Union Territories. While the French colony of Chandernagore was merged into the state of West Bengal in 1954, the other territories of France were brought under the Union Territory of Pondicherry (which also included Karaikal, Yanam and Mahe).

The five Portuguese territories of Goa, Dadra, Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu were also added to the list of Union Territories after their liberation in 1961. The Goa, Daman and Diu (Administration) Act, 1962 designated all three regions as one Union Territory even though they were about 1400 kilometres away from each other.

However, given that Goa was a prosperous region, it was soon sought after by the neighbouring states of Maharashtra and Mysore. It was only in 1987 that the Parliament passed the Goa, Daman and Diu Reorganisation Act granting statehood to Goa. Daman and Diu were retained as a separate Union Territory. A further change was brought about in their status once again in 2019 when the government merged Dadra, Nagar Haveli with Daman and Diu to form a single Union Territory, with the objective of improving administration in these regions.

Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh too became separate Union Territories. A presidential order passed in August 2019 abrogated Article 370 which gave a special status to the state of Jammu in Kashmir. The state was integrated with India and brought on equal footing with other units of the Indian Union. This was soon followed by the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Bill which would divide the state into two union territories — Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh.

References

Ali, Saiyid Fazil, Madhava Pannikar, and Hriday Nath Kunzru. ‘Report of the States Reorganisation Commission’. Government of India, 1955.

Guha, Ramachandra. India after Gandhi: The History of the World’s Largest Democracy. Indian ed. London: Picador India, 2008.

Kumar, Sudhir. Political and Administrative Setup of Union Territories in India. 1st ed. New Delhi, India: Mittal Publications, 1991.

Mawdsley, Emma. ‘Redrawing the Body Politic: Federalism, Regionalism and the Creation of New States in India’. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 40, no. 3 (November 2002): 34–54.

Sharma, Sudhesh. Union Territory Administration in India. Chandi Publishers, 1968.

Singh, Mahendra. ‘Reorganisation of States in India’. Economic and Political Weekly 43, no. 11 (12 March 2008): 70–75.

Srinivasan, Venkataraghavan Subha. The Origin Story of India’s States. Gurugram, Haryana, India: Ebury Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House, 2021.

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05