- India

- International

From Nav Nirman Andolan to anti-CAA protests: How student movements shaped Indian politics

A new rule in JNU to penalise students for protesting inside campus brings to attention the role that student movements have played in shaping local and national politics in India. These student movements also produced a generation of politicians, including former vice-president Venkaiah Naidu, former finance minister Arun Jaitley, and Union minister Nitin Gadkari, among others.

Student movements have been the catalyst for social and political changes in India.

Student movements have been the catalyst for social and political changes in India. In November 2023, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) administration announced that it will penalise protests on campus with a fine of Rs 20,000 or expulsion for two semesters. The JNU students’ union opposed the rules, saying that it is an attempt to stifle dissent on campus.

JNU’s new rule brings back attention to the role of students’ protests in local and national politics in India since the pre-Independence era.

In the article, The History of Student Movements in India: A Sociological Account, sociologist Amit Kumar Saurabh writes that student movements “have always been a catalyst of change in Indian society”.

The beginning of student movements

Student movements in India began in the 19th century after the establishment of important colleges including the Hindu College in Calcutta and Madras University. Historian SK Ghosh, in the book The Student Challenge Round the World, suggests that universities encouraged students to be actively involved in social and cultural causes, thus giving birth to student organisations.

In 1828, the Academic Association, the first student organisation that held weekly meetings and cultural events was started by Vivian Derozio in Calcutta. Sociologist Anil Rajimwale writes that the Academic Association was set up as a debating society, but Derozio was involved in several social reform movements during the Bengal Renaissance. Under his leadership, the association questioned the practice of Sati and advocated for widow remarriage.

However, it was the Partition of Bengal in 1905 that marked the first student movement where the leaders focused on expressing disagreement with government decisions. Following the Partition, many students dropped out of colleges affiliated to the University of Calcutta, and referred to the university as Golamkhana, a factory that produced trained slaves to support British rule in India. No longer did they propagate the ideologies of the larger reform movement and instead began dabbling in national politics.

The students were spirited and often used violence to express dissent. This changed with the spread of Mahatma Gandhi’s message of non-violence. The non-cooperation movement in 1919 was the first political movement in the country to witness substantial student involvement. It provided an impetus for youth leaders to hold the first All India Student Conference in 1920 and coordinate growing student movements across India.

Historian Philip Altbach, in an article written in 1966, explains that this conference ushered students into the spirit of nation-building and trained a set of young leaders such as Aruna Asif Ali and Matagini Hazra who went on to play an important role in the Independence struggle.

In the 1930s, as the freedom struggle intensified, the civil disobedience movement saw unprecedented involvement of students. Recognising that the universities were also run by the British, students refused to attend college, leading to suspensions and imprisonments.

However, this did not deter the students. Instead, it paved the path for the formation of the All-India Students’ Federation (AISF) in 1936. Several other organisations such as the All India Muslim Students’ Federation and Hindu Students’ Federation were also formed during this time. Altbach explains that the reason for students’ movements becoming political in nature was the Independence movement. The challenge was to ensure that the same spirit remained after Independence.

Student movements post-Independence

The radical fervour in student organisations, however, collapsed after Independence. National parties including the Congress now wanted students to distance themselves from politics.

Economist Surajit Mazumdar in a 2019 article writes that in the years immediately after Independence students thought of education more as a means to economic upliftment rather than as a space for free thought. The idea that students must be involved in nation-building rather than politics and the parallel strengthening of the social attitudes of the Indian middle class together worked towards the depoliticisation of university education.

Additionally, the education system was also expanding. A report Progress of Education in India published by the Economic and Political Weekly in 1965, states that between 1950s and 60s, the number of arts and sciences colleges grew from 498 to 1,039 and the enrolment doubled from 310,000 to 691,000. With the influx of an entirely new social strata of youth, the issues of the student movements also changed. Regional political issues like the linguistic division of states, interested the students, leading to more localised protests.

The student movements reemerged in the 1960s after an armed peasant revolt shook a small village of Naxalbari in West Bengal. Peasants tired of oppression from feudal landlords launched a rebellion in 1967. They tried to take over agricultural land as a means of protest but were arrested by the police. Under the leadership of Charu Majumdar,the Naxal uprising caught the attention of the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPI-M) who wanted to bring about a socialist revolution.

Students at the University of Calcutta, Presidency College and Delhi University hoisted the CPI-M flag and cut out stencil portraits of the Chinese Marxist revolutionary Mao on the college walls in response to the events unfolding in West Bengal and Hyderabad, where the Naxal movement had spread. In Presidency College, Jadavpur, some students also took to violence. Former IAS officer and Presidency College alumnus, Jawahar Sircar writes that the police dreaded entering the Bhabni Dutta Lane in Presidency College without adequate protection. The lane was infamous for vandalising college property and many protesters also used it as a space to hold meetings. The police would fire tear gas in Bhabni Dutta Lane and College Street to discipline the students.

Along with the Naxal movement gaining traction, the 1970s were a particularly turbulent time for Indian politics. The domination of the Congress Party was declining, Emergency was imposed and many student movements emerged.

The political shift in student movements

Scholars argue that the protests during the 1970s could attain national importance because they stemmed from local grievances such as hike in fees. One such movement was the Nav Nirman Andolan which began on December 20, 1973, when students of LD Engineering College, Gujarat called for a protest against a 40 per cent hike in mess charges.

Historian Bipin Chandra, in the book In the Name of Democracy: J.P. Movement and the Emergency, writes that the students blamed the price rise on the collusion between traders, black marketeers and politicians. Chief Minister Chimanbhai Patel was accused of having entered into a deal with groundnut oil traders to hike oil prices in return for donations to party funds.

These accusations came at a time when severe drought had already caused the failure of two cycles of crops. As the protests began, the students set fire to the college canteen and attacked the Rector’s house, leading to the arrest of several students.

But this did not deter other students who went on strike demanding the release of the arrested students, a reduction in mess charges, the resignation of the minister of education, and the arrest of everyone responsible for price rise. Although the government, in an attempt to appease the protesters, released all the arrested students, the movement did not halt.

Student leaders called for an indefinite strike in all schools and colleges across the state. On January 11, 1974, many groups of protesters came together to form Nav Nirman Yuvak Samiti and thus began the Nav Nirman movement, seeking the resignation of the entire government.

Owing to pressure, Chief Minister Patel resigned on February 9, 1974, and President’s rule was imposed. Researcher Varsha Bhagat-Ganguly in an article explains that the students visited the MLAs of each constituency and demanded resignations. Each time the ministers and MLAs declined, the students painted their faces black and shaved their heads in protest.

Leaders like Morarji Desai also joined the movement and began a fast unto death for the dissolution of the government. Prime Minister Narendra Modi too took part in the Nav Nirman movement. While he was not part of the Samiti, he participated in the protests and later joined Janata Party leader Jayaprakash Narayan’s Lok Sangarsh Samiti as General Secretary.

Finally, on March 16, 1974, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi dissolved the assembly and announced elections in September.

Impressed by the Nav Nirman movement, Jayprakash Narayan encouraged the Chhatra Sangarsh Samiti (CSS) in Bihar to demand the resignation of the Abdul Ghafoor-led Congress government. (Express Archives)

Impressed by the Nav Nirman movement, Jayprakash Narayan encouraged the Chhatra Sangarsh Samiti (CSS) in Bihar to demand the resignation of the Abdul Ghafoor-led Congress government. (Express Archives)

The Nav Nirman Samiti disintegrated soon after elections but the resounding effect of the movement remained in Gujarat. Impressed by the Nav Nirman movement, Jayprakash Narayan encouraged the Chhatra Sangarsh Samiti (CSS) in Bihar to demand the resignation of the Abdul Ghafoor-led Congress government. On March 18, 1974, Jayprakash along with students entered the Bihar legislature and tried to block the governor from addressing the legislators. It led to violent clashes which left eight dead and 78 others injured. Although the CSS movement failed to achieve its objective, it, along with the Nav Nirman movement, sculpted a political consciousness among the youth that was crucial in the student resistance during the Emergency.

The Emergency

On June 25, 1975, Indira Gandhi imposed Emergency, worsening the already delicate political climate of the country. The government took several steps to curb student agitations. Many student leaders were jailed, thrown out of universities or denied admission. Student Unions were banned and organisations were reduced to only cultural activities.

Sociologist N Jayram, in the research paper Sadhus no longer: Recent Trends in Indian Student Activism (1979), cites the example of Hemant Kumar Vishnoi Kumar, who was the Secretary of the Delhi University Students Union (DUSU) and was associated with the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP). Vishnoi had won the student union election on the issues of the Gujarat and Bihar movements and the government was on the lookout for him. Vishnoi, along with 50 other leaders, was arrested on July 25, 1975.

Jayram says Vishnoi’s arrest reflects the state’s open crackdown on student leaders across the political spectrum.

Mass protests ensued after Vishnoi’s arrest. The Sangharsh Samiti, another student organisation in Delhi, issued pamphlets condemning the arrests and observing July 25, the day of the raids, as ‘Close the University Demand Day’.

Jayram writes that Vishnoi and his associates were tortured to reveal secrets about the underground movement. To cover all bases, some intelligence agents also enrolled in institutions to discover the secret structure of student activism. However, the government could not restrain the student resistance for long.

Once the 1977 Lok Sabha elections were announced and student leaders were released, they campaigned aggressively against the Indira Gandhi government. The Congress Party lost the election paving way for the Janata Party to assume power and Morarji Desai became the Prime Minister.

Student resistance during the Emergency launched the career of former finance minister Arun Jaitley

Student resistance during the Emergency launched the career of former finance minister Arun Jaitley

Student resistance during the Emergency also produced a generation of politicians like former vice-president Venkaiah Naidu, former finance minister Arun Jaitley, and Union minister Nitin Gadkari, among others.

Agitations in Northeast

The post-Emergency period saw the rise of regional movements, primarily driven by issues of ethnic conflict and illegal immigration.

In Assam, issues such as development and ethnic identity became central for student movements. The ‘Assam Movement’ began in 1979 and went on till 1985. Under the leadership of youth leader Prafulla Kumar Mahanta, the protesters demanded the Indian government identify and expel illegal immigrants. All Assam Students Union (AASU), which was founded in 1967 at Guwahati University and the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) spearheaded these protests. On June 8, 1979, the AASU conducted a 12-hour state-wide bandh to demand the “detection, disenfranchisement and deportation” of foreigners.

Political scientist Sanjib Baruah in the book Indian Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality (1999) writes that the Assam student movement gained momentum because of their protests against illegal immigrants.

Baruah writes that in November 1979, nearly 700,000 people in Guwahati and twenty lakh people across the state organised satyagraha. Students would walk into the government offices, court arrest, and be released a few hours later.

In 1980, ethnic clashes ensued and the All Assam Minorities Student Union (AAMSU) came into being which demanded that everyone who came to Assam before 1971 must be granted citizenship. AASU and AAMSU found themselves in opposition to each other and violent conflicts between the two followed.

With violence continuing well into the mid-1980s, a resolution was deemed necessary. On August 15, 1985, the Rajiv Gandhi-led central government signed the Assam Accord with AASU leader Prafulla Mohanta. The accord allowed foreigners, who came to India after 1st January 1966 but before 25th March 1971, to seek Indian citizenship. Once the accord was signed, the state Assembly was dissolved and fresh elections were held in December 1985. Mohanta became the youngest Chief Minister in independent India at the age of 32.

On August 15, 1985, the Rajiv Gandhi-led central government signed the Assam Accord with AASU leader Prafulla Mohanta.

On August 15, 1985, the Rajiv Gandhi-led central government signed the Assam Accord with AASU leader Prafulla Mohanta.

The Assam Movement mobilised other student organisations in the Northeast. The All Nagaland College Students’ Union (ANCSU) and Khasi Students Associations also fought for issues of tribal identity and culture. In the 1980s, they organised several rallies, which led to three violent clashes between the tribal and non-tribal people. In Arunachal Pradesh, student movements were centred around the state of education, student rights and employment. In 1980, the Arunachal Pradesh Student Union (APSU) called for a two-day state bandh for 80 percent reservation in jobs for Arunachalis.

Anti-Mandal agitation

The 1990s witnessed a change in the mechanisms of student movement. The Anti-Mandal agitation is one such movement, which also brought caste into mainstream Indian politics.

The 1960s and 1970s had seen a rise of the ‘backward castes’, such as the Jats in Punjab and Haryana, and the Vokkaligas in Karnataka. Land reforms in the 70s granted them economic power. However, they were not strongly represented in administrative positions.

To assess this situation, the Morarji Desai-led central government appointed the Backward Classes Commission in 1979, known as the Mandal Commission. The Commission identified that Other Backward Castes (OBCs) filled only 12.5 per cent of all administrative posts in the central government.

As a solution, the Mandal Commission recommended that 27 per cent of all posts in the central government should be reserved for OBCs. This was in addition to the already 22.5 per cent reservation for Scheduled Castes and Tribes. When VP Singh became the Prime Minister, he issued an order implementing 27 per cent reservation for OBCs for all central government jobs from August 13, 1989.

India witnessed violent protests opposing the reservations. Political scientist Simanti Lahiri, in the book Suicide Protests in India: Consumed by Commitment (2014), writes that for a month upper-caste and class individuals protested through strikes and rallies. In the absence of any strong student union or association, the protests were scattered but intense enough to build pressure.

On September 19, Rajiv Goswami, a student of Deshbandhu College, attempted self-immolation. It sparked a series of self-immolation attempts across university campuses. Over 100 students attempted suicide and at least 60 died. The protests slowly died down. After the elections in 1991, the Congress rose to power again and PV Narasimha Rao became Prime Minister, and the Mandal Commission report was implemented in 1992.

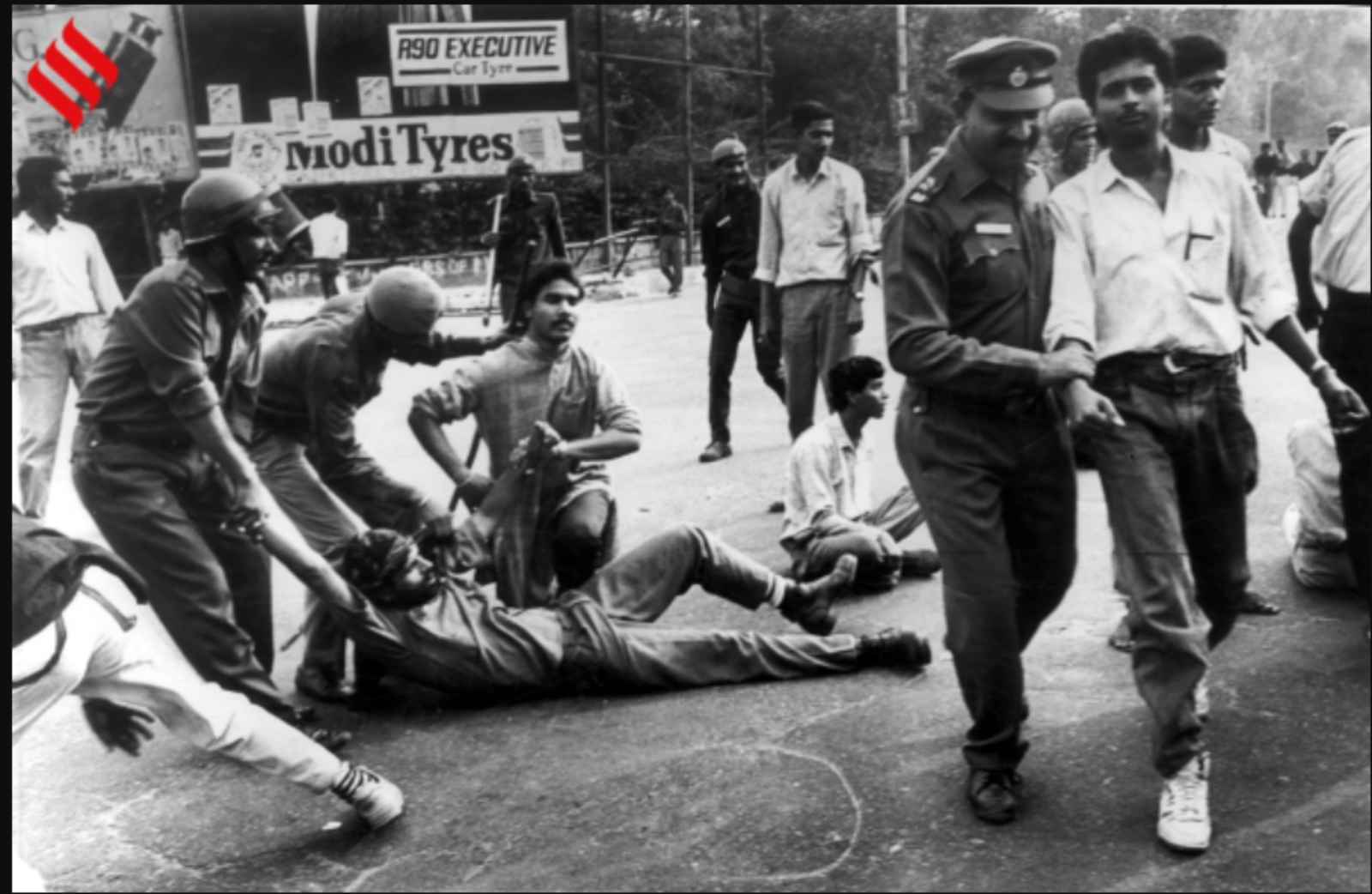

Students in Delhi being arrested during the anti-Mandal protests (Express Archives)

Students in Delhi being arrested during the anti-Mandal protests (Express Archives)

The birth of Dalit students groups

The Mandal agitation paved the way for students from marginalised communities to form organisations on university campuses.

The Ambedkar Students Association (ASA) came into being in 1993 at the University of Hyderabad. While Dalit activism was strong in universities of South India since the 1970s, the Mandal agitation made caste a central issue in campuses like JNU in Delhi. The United Dalit Students’ Forum (UDSF) was formed by SC and ST students on account of a lack of representation in dominant student politics.

A 2016 Frontline editorial argued that the rise of Dalit student organisations did not just focus on the plight of Dalit students but also brought Ambedkar’s ideology and political thought to the forefront.

The Dalit assertion was stronger in southern campuses like Hyderabad Central University as compared to JNU. PhD scholar Rohith Vemula’s suicide in 2016 was a stark reminder that caste discrimination persists, despite affirmative action programmes in university spaces.

Student movements in neo-liberal India

Unlike the political turbulence of the 1960s and 1970s that witnessed student movements as a response to these changes, globalisation has rendered new ways of engaging with politics.

Yet, many protests have received national attention and have drawn from earlier student agitations. The infamous 2016 JNU Azadi protests launched leaders like Kanhaiya Kumar and Umar Khalid to the national stage. The slogans used during the protests were reminiscent of previous student agitations such as the Nav Nirman and Mandal protests.

The last student movement was the protests against the National Register of Citizens and Citizenship Amendment Act (NRC-CAA) in 2019. On December 13, 2019, thousands of students gathered at Jamia Millia Islamia to protest the implementation of the CAA-NRC. The students argued that while the intentions of the bill to provide refuge for Hindu, Sikhs and other minority religions in neighbouring countries citizenship in India is laudable, they found it troubling that religion was the basic legal criterion for citizenship.

Many protesters were arrested and booked under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). Similar agitations took place in other universities across India. Ignited by students, the protest soon became a national movement with Shaheen Bagh as its epicentre. The intensity of the movement was cut short by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

The anti-CAA protests started out from Jamia Milia Islamia. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

The anti-CAA protests started out from Jamia Milia Islamia. (Express Photo by Gajendra Yadav)

The anti-CAA protests in some ways also brought together a wide section of the student population. Earlier agitations like the Mandal protests, the Dalit assertion and the Northeast movement often had homogenous groups of students across caste and class lines. The anti-CAA protests blurred these distinctions and brought together people from diverse communities.

The rich history of student movements in India have shaped both local and national orders. As political scientist Seymour Lipset in his book, Revolution and Counterrevolution says, “students have remained a source of radical leadership and mass support when other elements of society have not”.

References

- Altbach, Philip. The Transformation of the Indian Student Movement. Asian Survey 6, no. 8 (1966): 448–60.

- Chandra, Bipan. In the Name of Democracy: JP Movement and the Emergency. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

- Ganguly, Varsha-Bharat. Revisiting the Nav Nirman Andolan of Gujarat. Sociological Bulletin 63, no. 1 (n.d.): 95–112.

- Ghosh, Srikanta. The Student Challenge Round the World. Eastern Law House, 1969.

India against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality. 5th impr. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010. - Jayaram, N. Sadhus No Longer: Recent Trends in Indian Student Activism. Higher Education 8, no. 6 (November 1979): 683–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00215990.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. Revolution and Counterrevolution: Change and Persistence in Social Structures. Rev., with A new introduction. New Brunswick, N.J: Transaction Books, 1988.

- Mazumdar, Surajit. The Post-Independence History of Student Movements in India and the Ongoing Protests. Postcolonial Studies 22, no. 1 (2 January 2019): 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2019.1568166.

- Rajimwale, Anil. Student Movement in India in the Nineteenth Century. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 49 (1988): 343–48.

- Saurabh, Amit Kumar. The History of Student Movements in India: A Sociological Account. The Oriental Anthropologist: A Bi-Annual International Journal of the Science of Man 23, no. 1 (June 2023): 147–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/09754253221122759.

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05