- India

- International

The mystery of the Indus script: Dravidian, Sanskrit or not a language at all?

For more than a century now, over one hundred attempts have been made by scholars from different fields to decode the Indus script, without much success. The many theories include those that link the language to Sanskrit, Dravidian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian among others. There are also those that are skeptical about whether the Indus script is in any one language at all.

A representational image of ancient scripts and seals created by Dall-E

A representational image of ancient scripts and seals created by Dall-EEver since the remains of the Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC) was first discovered in the 1920s by a team of British archaeologists led by Sir John Marshall, its script has remained a puzzle. For about a century now, more than 100 attempts have been made by archaeologists, epigraphists, linguists, historians, scientists and others to decipher the script without much success. A recent research paper published by a Bangalore-based software engineer contends that the Indus script was mainly written with signs that could symbolically convey meanings to people of different dialects, and languages, across Indus settlements.

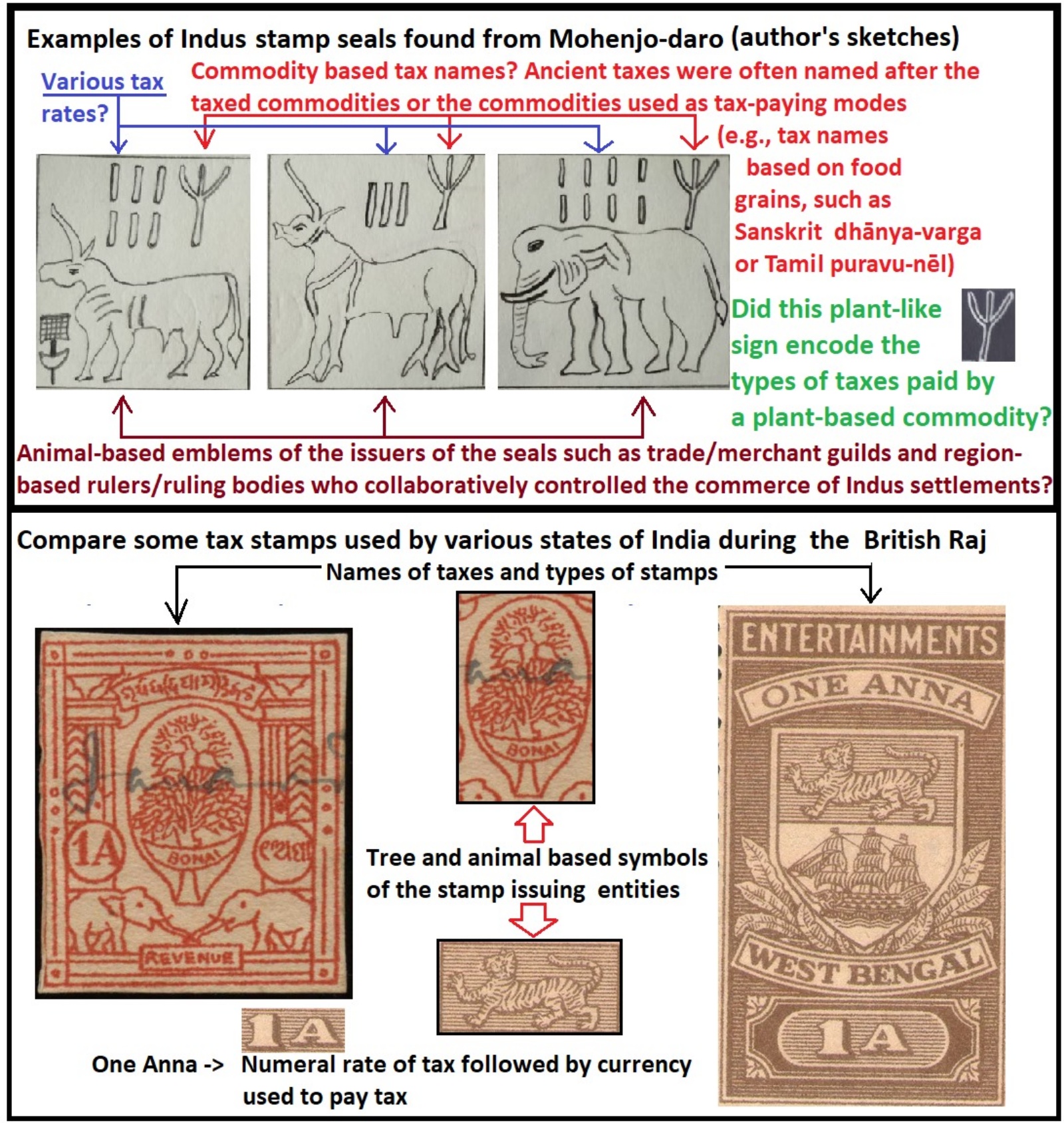

Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay, who has been researching the Indus script since 2014, contends that each Indus sign represented a specific meaning, and the script was used mainly for commercial purposes. In a paper published in the Nature Group of journal – Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, volume 10, Article number: 972 (2023), Mukhopadhyay explains that the inscribed Indus seals were mainly used as tax stamps, while the tablets were used as permits for tax collection, craft making or trading. She argues that contrary to popular beliefs, the script was not used for religious purposes, nor did it phonetically spell out words to encode names of ancient Vedic or Tamil deities. “Any such attempt of reading the Indus script is inherently flawed,” she suggests.

While Mukhopadhyay’s arguments are far from being accepted universally, it has definitely caused a stir among the small but diverse group of scholars who have been studying and attempting to decode the Indus script and language for years.

Debating the Indus script

The Indus Civilisation reached its peak between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE, spread out over an expansive area of about 800,000 square kilometres in large parts of modern-day Pakistan and north-western India. Scholars agree that at its time it was the most extensive urban culture in the world with an elaborate trade, taxation and drainage system.

Examples of Indus signs compiled by Bahata Mukhopadhyay

Examples of Indus signs compiled by Bahata Mukhopadhyay

The inscriptions left behind by the Indus culture occur on seal stones, terracotta tablets and occasionally on metal. They are written in pictograms often in conjunction with animal or human motifs. To begin with, scholars have for long disagreed and debated over the number of symbols that the Indus script contained. Archaeologist S R Rao had in 1982 postulated that the script contains just 62 signs. This was refuted by the Finnish Indologost Asko Parpola, one of the most formidable names associated with the decipherment of the Indus script. He put the number at 425 in 1994. As recently as 2016, archaeologist and epigrapher Bryan K Wells suggested a much higher estimate of 676 signs.

The issue of the language on which the Indus script is based is yet again something that scholars cannot agree upon. Long before the ruins at Harappa and Mohenjodaro were even recognised as part of the Indus Valley Civilisation, Sir Alexander Cunningham had reported the first seal from Harappa. A few years later he had suggested that the inscriptions on the seal bear signs of the Brahmi script which is the ancestor of more than 200 scripts in South and Southeast Asia. After Cunningham, several other scholars too made the argument in favour of connecting the Indus script with Brahmi.

Parpola, who is Professor Emeritus at University of Helsinki, disagrees with this hypothesis. “The Brahmi script emerged on the basis of the Aramaic script used in the Persian Empire,” he says.

He explains that it is an alphabetic script that was brought to the Indus Valley by the bureaucrats of the Persian Empire in 500 BCE and that the Brahmi script was further influenced by the Greek script which came to India with Alexander the Great in 326 BCE. Consequently, it could not have had anything to do with the Indus script given that the civilisation had died down much before.

There was also the attempt made by a few scholars to connect the Indus script with Sanskrit. The most notable voice in this regard was that of archaeologist SR Rao who is credited with having discovered some very important Harappan sites such as Lothal. Rao’s argument was seen as a product of ideological bias by several scholars. Journalist and author Andrew Robinson, in his book Lost Languages: The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts (2008), writes “it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Rao, for nationalistic reasons, was determined to prove that the Indus language was the ancestor of Sanskrit, the root language of most of the modern languages of North India, and that Sanskrit was therefore not the product of the so-called Indo-Aryan (Indo-European) ‘invasions’ of India from the West via Central Asia but was instead the expression of indigenous Indian (Indus) genius.”

“There is archaeological evidence to suggest that the Aryans came to Indus Valley only in the second millennium BCE which is after the Indus Valley Civilisation,” explains Parpola with regard to why Sanskrit could not have been connected with the Indus script.

Parpola’s own investigation into the Indus script began in 1964 while he was working on his doctoral thesis on Vedic texts. It started out more as a hobby, as he was inspired by the deciphering of the Greek Linear B script that had taken place just a decade back. One major innovation he brought to the field of the Indus script was the use of computers which was a new technology back then. Along with his childhood friend Seppo Koskenniemi who was a computing expert and his brother Simo Parpola who was then working on the Mesopotamian cuneiform script, the trio began studying the Indus script. The team’s analysis reached the conclusion that the script had Dravidian roots.

In a zoom interview with indianexpress.com, Parpola explains that this is a logosyllabic script of the kind used by all major cultures around 2500 BCE. “Basically the signs were pictures which stood for complete words by themselves,” he says. He argues that the script used the concept that we now know as ‘rebus’, that is either the pictogram meant the word for the object or action depicted, or any word that sounded similar to that word, irrespective of meaning. “So if we know the language on which the script is based then we have the possibility of deciphering some signs of the script,” Parpola says.

An example he cites of his decipherment is that of the fish sign that is found in abundance in the Indus seals. “It is unlikely that they are speaking about actual fish in seal texts,” he says. He then connects it with the Dravidian word for fish, ‘min’. This word ‘min’ has a homophone ‘min’ meaning ‘star’ which he believes is what the Indus sign is denoting in seals, given that in pre-Vedic times it was common practice for people to have astral names. Starting from this basis, Parpola claims to have found the Old Tamil names of all the planets in the Indus script.

Parpola’s hypothesis has found support among several scholars, both in the West and in India including that of Iravatham Mahadevan, the leading Indus script researcher in India.

Even those like Mukhopadhyay who are doubtful about whether the Indus script was based on any one language at all, say that linguistic evidence indicates that the Indus people most likely spoke a Dravidian language. Linguist Peggy Mohan, who has been working on the language of the Indus Valley, says that “this was most probably a Dravidian society, but with a language family a bit different in some of its details from the Dravidian we now know in the South.”

There were also attempts to connect the Indus script with other cultures with whom the people of the Indus Valley were possibly in trading relations. One of the first decipherments that was published in 1932 by the Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie suggested that the Indus script be treated on the pictographic principles that were followed in Egyptian hieroglyphs. In 1987, an Assyriologist J V Kinnier Wilson argued for links between the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia.

Yet another attempt was made by an Hungarian engineer, Vilmos Hevesy, who in 1932 suggested a connection between the Indus inscriptions and the rongorongo tablets of Easter Island in the Pacific Ocean. Parpola, who finds Hevesy’s theory to be the ‘strangest’ of all, argues in his book, The Roots of Hinduism (2015), that “the two scripts are separated by more than 20,000 kilometres and some 3500 years.” Moreover, he writes that the speculation is useless given that the rongorongo tablets are to a large extent undeciphered.

Is the Indus script based on a language at all?

Since the early 2000s, some researchers have been questioning if the Indus script was a language at all. This hypothesis was based mainly on the fact that the Indus inscriptions found are all very short. On an average there are about five characters per text and the longest is 26.

The issue was hotly debated after a group of researchers consisting of historian Steve Farmer, computer linguist Richard Sproat, and Indologist Michael Witzel came out with a paper in 2004 titled The collapse of Indus Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilisation. In it they claimed that the Indus script did not constitute a language-based writing system and that they were mainly nonlinguistic symbols of political and religious significance. The paper refuted the universally accepted claim that the Indus Valley was a literate civilisation. It also accused those who link the script to Dravidian or Sanskritic roots of being ideologically motivated. “Political motives linked to the Dravidian and Indo-Aryan models, often obscured under a thick veneer of ‘neutral’ scientific language, have played an increasing role in the Indus script thesis in the last two decades,” they noted. However, they also pointed out that “evidence that Indus inscriptions did not encode speech increases and does not decrease the symbols’ historical value.” “We know a great deal about literate civilisations, but far less about premodern societies that rejected writing for other types of sign systems,” they wrote.

The theory devised by the team came to be severely criticised by many scholars, both for its tone and for its findings. Parpola, for instance, points out to the principle claim made by the team that all writing systems have produced longer texts than those found in the Indus script. He notes that even Egyptian hieroglyphic writing was of a similar nature.

Mukhopadhyay, whose recent findings have led to similar conclusions, says even though she partly agrees with the technical arguments being made by Farmer and his team, she does not approve of their tone and definitely does not consider the Harappans to be ‘illiterate’. “The script’s symbols are influenced by linguistic symbolism in certain cases.” she says. “But they do not phonologically spell words of any language. The script also has a language like syntax, as it uses connective signs and certain phrase orders.”

Mohan, who is in support of Mukhopadhyay’s views, says we must stop calling it the Indus ‘script’ and consider it something like a hallmarking system. “Even today dhobis in India have their own signs which are useful for them but they are not what you would call language,” she says. She emphasises the need to form a distinction between the script and the language. “Most prehistoric societies did not write the kind of things we write today. Commercial information was perhaps the first thing that any society would record in writing,” she says. As she points out, stories and mythologies would be memorised, passed down and reinvented through generations, not necessarily written.

As far as the language of the Indus people is concerned, Mohan suggests that the Indus Civilisation was spread across a vast area. It is highly unlikely that the people spoke a single, uniform language. “Linguists put too much emphasis on words to find a language. I don’t like this approach. You and I are speaking English right now, does that make us British?” she asks, adding that “words by themselves are transferable and don’t tell us everything about a society.”

Italian archaeologist Paolo Biagi too doesn’t believe that the Indus script is strictly related to any language. He recollects his experience of being a member of an archaeological mission in Oman in the 1990s, where they found an Indus inscription at one of the sites. “We started excavating further with the hope of finding something bilingual since Oman is located between the Indus Civilisation and Mesopotamia,” he says. “But we never found anything in terms of language, even though we found other traces of trade between Indus and Mesopotamia.”

Parpola, though, remains skeptical of the view that the script did not represent a language. “I believe that a script is always there to write a language,” he says. He also points out that it would be an error to assume that the script is not encoding proper names or names of deities.

Mukhopadhyay notes that whenever any ancient script is found, people feel very romantic about it. “They hope to find things like old scriptures or poetry. Even when Linear B was being deciphered, some scholars hoped to find snippets of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. But what they found was a record of palace book keeping of the things that were brought in and those that left the palace,” she says. But that does not take away from the findings that they led to the discovery of a lot of other information about the palace economy. “Similarly, in the case of the Indus script, even though it is just giving us commercial information, it can tell us a lot about how the economy functioned at that time,” Mukhopadhyay adds.

Biagi is of the opinion that the main challenge in deciphering the Indus script is the fact that we still don’t know enough about the civilisation itself. “Most of the excavations carried out, especially in Pakistan, are very old. For instance, Mohenjodaro was excavated more than (one) hundred years ago and we use far more advanced ways of examining and recording findings today,” he says. Further, a large number of Indus sites are still lying undiscovered. “We know about how civilisation disappeared, but what do we know enough about its origins?” he asks.

Further reading:

Asko Parpola. The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. 2015

Andrew Robinson. Lost Languages:The Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts. Tess Press. 2008

Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay. Semantic scope of Indus inscriptions comprising taxation, trade and craft licensing, commodity control and access control: archaeological and script-internal evidence. Nature. 19 December 2023

Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat, Michael Witzel. The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization. Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 21 June 2016

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05