- India

- International

From Shivaji to Shinde, how Marathas came to dominate Maharashtra politics

The term ‘Maratha’as a category or caste is an amalgamation several different castes, most of whom occupied the lower strata of the caste hierarchy such as the Kunbi, Lohar, Sutar, Bhandari, Thakar and Dhangar. Adrija Roychowdhury finds out about the complex historical process through which the Marathas became a distinct caste.

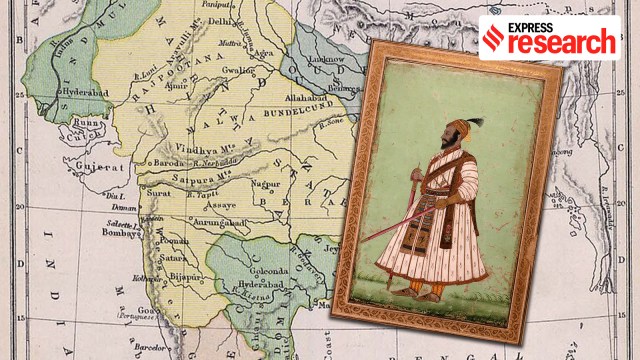

In the late 17th century, Shivaji carved out his own independent Maratha Empire that expanded its control over large parts of the Indian subcontinent through the 18th century.

In the late 17th century, Shivaji carved out his own independent Maratha Empire that expanded its control over large parts of the Indian subcontinent through the 18th century. The political conflict over whether the Marathas are a “backward” community or not has been raging since the early 1980s. Historians have long agreed that the term ‘Maratha’ as a category or caste is an amalgamation of families from several different castes, most of whom occupied the lower strata of the caste hierarchy such as the Kunbi, Lohar, Sutar, Bhandari, Thakar and Dhangar. It is over a period of three or four centuries and through a complex historical process that Marathas acquired a distinct caste identity that went on to dominate the political and economic landscape of modern Maharashtra. “The Marathas are a self-empowerment success story in modern India,” says anthropologist Thomas Hansen who has authored the book, ‘Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay’ (2018).

The history of the emergence of Marathas as a distinct caste

The story of the Marathas begins sometime around the 14th century with the Muslim invasions of Maharashtra. The initial raid into the Deccan was carried out by Alauddin Khilji in the late 13th century. Since then and till the 1350s a period of intense conflict followed in the Deccan, ending with the establishment of the Bahmani Sultanate. The Muslim dynasties that stayed in power in the Deccan for the next 350 years were crucial in determining social mobility in the region. Historian Steward Gordon, in his authoritative text on the Marathas, explains that “those who prospered during these centuries came to be termed Marathas.”

As Gordon notes in his book, it is difficult to explain how the term ‘Maratha’ arose in the first place. Unlike, say, the term ‘Bengali’ that refers to Bengali-speaking people, not all Marathi-speaking people were Marathas. From the 14th century though, the term increasingly came to be applied to refer to a new elite or the Maratha chiefs who brought bands of followers to serve the military of the Bahmani kingdom and the Sultanates that it gave rise to.

The Maratha category comprised several castes. What unified them though was the martial tradition which they were proud of and the rights and privileges they obtained from military service. “It was these rights that differentiated them from ordinary cultivators, ironworkers or tailors, especially at the local level,” writes Gordon. He draws a parallel with the origin and development of the term ‘Rajput’, whose martial tradition had developed through service to the Mughal Empire. Eventually, Maratha caste identity, like that of the Rajputs, was cemented through kinship and marriage restrictions.

The Maratha identity acquired further currency with the emergence of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, who himself belonged to the Bhonsle Maratha clan. Shivaji’s father, Shahaji Bhonsle, was a Maratha general who served the Deccan Sultanate. In the late 17th century, Shivaji carved out his own independent Maratha Empire that expanded its control over large parts of the Indian subcontinent through the 18th century. The reign of Shivaji, and particularly the Marathas’ defeat of the Mughal army, has for years served as the historical justification for political dominance in the region.

The process of empowerment of the Marathas was not an easy one though. Hansen explains that “even during the time of Shivaji, there was a constant dispute with the local Brahmins over whether the Marathas ought to be accorded Kshatriya status or whether they were Shudras.” By the 19th century, most of the princely states, particularly in Western Maharashtra, came to be ruled by Maratha aristocracy, who then became involved in the non-Brahmin movement.

Marathas and the non-Brahmin movement

It is the non-Brahmin movement of the late 19th century that really defines the Maratha identity in opposition to the Brahmins. In 1873, at a time when several social reform movements had blossomed across India, the Satyashodhak Samaj (truth-seeking society) was founded by Jyotirao Phule in Pune. Inspired by Western utilitarian philosophy and Christianity, Phule constructed a historical narrative suggesting that the Deccan society evolved from a community of Shudra peasants. As described by Hansen in his book, Phule believed that an egalitarian, harmonious society was maintained by the Shudras in the pre-Aryan golden age era and that it was destroyed by the conquest and subsequent domination of the northern Aryan Brahmanical groups.

As noted by the celebrated American Ambedkarite anthropologist Gail Omvedt in her book, Cultural Revolt in a Colonial Society: The Non-Brahman Movement in Western India 1873-1930 (1976), the Satyashodhak Samaj “represented the aspirations of a wide range of non-Brahmin castes from Untouchables to the large agricultural caste of Maratha-Kunbis.”

Jyotirao Phule established the Satyashodhak Samaj in 1973 (Wikimedia Commons)

Jyotirao Phule established the Satyashodhak Samaj in 1973 (Wikimedia Commons)It created a network of educational institutions, publications and charity trusts independent of Brahmanical support in the provincial cities of the Deccan. Leaders of the non-Brahmin movement were in fact initially opposed to the Brahmin-dominated nationalist movement that they saw as “an attempt to replace British rule by Brahmin rule. (Omvedt,1966)”

From the 1920s onwards, the non-Brahmin movement introduced the Chhatrapati mela, celebrating the valour of Shivaji. As described by Hansen in his book, “the songs and plays enacted in these melas ridiculed the Brahmins, their abuse of power and privilege in Pune, and praised the Marathas as the true people of Deccan and the nation.” In this, the non-Brahmins came in direct conflict with the Chitpavan Brahmin Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who in his attempt to combine Hindu orthodoxy with nationalism tried to promote Shivaji as a symbol of regional Hindu identity.

The Maratha elite, however, favoured the celebration of Shivaji initiated by the non-Brahmin movement. When Tilak approached the Maharaja of Kolhapur, Shahu Maharaj, a direct descendant of Shivaji, to obtain legitimacy and funding for the celebration of the erstwhile Maratha emperor, he received no response. The Maharaja was staunchly opposed to Tilak and the Pune Brahmins and instead lent his support to the festival organised by the Satyashodhak Samaj. Hansen notes that it is through these competing narratives that the cult of Shivaji spread across the Bombay presidency.

From 1900 itself the non-Brahmin movement came under the leadership of Shahu Maharaj. Under him, the Satyashodhak Samaj began to define the Marathas as a broader social category. By the 1920s, when Shahu left the organisation, the Satyashodhak ceased to exist, but the impact of the mobilisation they had done was irreversible. Brahmins and Marathas had turned into defined collective identities.

This was accompanied by the interventions of the colonial authorities who were keen on favouring the non-Brahmin movement in opposition to the nationalist struggle being mobilised under Brahmanical control. “The British looked at the Maratha leaders as possible allies against the tide of nationalism,” explains Hansen. “It was part of the colonial policy to empower the Maratha peasantry.” Right up till the Second World War, the Marathas along with the untouchable Mahar community were preferred recruits in the colonial army and the Bombay police.

With electoral democracy emerging in the 20th century, caste politics became a number game. Historian Sumit Guha explains that traditionally caste would operate in small groups centred around practices of touch, food and marriage. In the electoral system though, where there are millions of voters, the traditional caste identities are not useful. Rather, larger networks of regional caste identities get mobilised to get voters out. “It is out of these electoral processes that larger voting blocs around caste emerge,” he says. Older names like the Marathas then assumed a wider political significance.

Omvedt notes that by the end of the 1920s, an extensive rural leadership had developed that was not based on traditional authority, but on the ability to express educational and economic demands of non-Brahmins. Being identified as a Maratha was increasingly becoming an attractive affair. Hansen in his book observes that in the District Gazetteer of Thane in 1882, Kunbis, Agris, Kolis were identified as distinct caste groups and with each group the elite layers were characterised as Marathas- Maratha-Kunbi, Maratha-Agri and the like. By the 1931 Census, however, Marathas and Kunbis were lumped together into a single category. Kunbi as a caste category itself seemed to have been disappearing and being co-opted in the mega caste identity of the Marathas.

Maratha dominance in Maharashtra politics

After the death of Shahu Maharaj, the non-Brahmin movement came under the leadership of Keshavrao Jedhe and Dinkarrao Jawalkar. In 1923, another member of the group, Bhaskarrao Jadhav formed the Non-Brahmin Party. Through the 1920s, members of the Non-Brahmin Party gained control over the local boards of several districts in Maharashtra such as Satara, Solapur, Nashik, and Buldhana. S M Dahiwale, in an article published in the Economic and Political Weekly in 1995, notes that “it is evident that wherever the non-Brahmin movement was strong, the non-Brahmins could wrestle power from the Brahmins.”

Jedhe and Jawalkar emerged as fierce critics of Tilak and Brahmins in politics. They demanded that all Brahmins be expelled from legislative councils, local bodies and services. In 1926, they disallowed Brahmins from joining their party. When BR Ambedkar led a satyagraha at Mahad in 1927, Jedhe and Jawalkar demanded that no Brahmin be allowed to participate in it. Ambedkar refused to go ahead with their condition on the ground that he was against Brahmanism but not against Brahmins.

By the 1930s, younger members of the Non-Brahmin Party started joining the Congress in its civil disobedience movement. Gradually, the political power mobilised by the Marathas in the rural districts started getting incorporated into the nationalist movement, leading to the alienation of the Brahmins from the Congress party in Maharashtra. Hansen in his book explains that in the post-Independence period, two events resulted in the ‘Maratha-isation’ of the Congress party. First, extension of universal adult franchise gave non-Brahmins and Marathas a large potential mass base. Second, the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi by a Chitpavin Brahmin, Nathuram Godse, released a wave of resentment and violence against Brahmins in the region. “Although part of this rage was spontaneous, it was also subtly encouraged by non-Brahmin Congress leaders who sought to establish their credentials in the party,” writes Hansen.

In the years to come, Marathas gained popularity in Maharashtra politics, be it in the demand for statehood or in electoral success. Since Maharashtra was formed in 1960, 12 out of its 20 chief ministers, including the incumbent Eknath Shinde, have been Marathas. Hansen says the political success of the Marathas in Maharashtra is similar to that of the non-Brahmin movement in Tamil Nadu or the Yadavs in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, except that in case of the former the process is much longer and deep-rooted.

Since the 1980s, when the Mandal commission report was tabled, the Marathas have been agitating for OBC reservation and demanding that they be identified as Kunbis. Over the years, consecutive Maharashtra chief ministers have been unable to satisfy the demands of the community. Hansen explains that the reservation issue is drawn from two sources — the seeming success of the Patels in Gujarat some years back to attain reservation and the fact that Maratha is no longer a unifying label of the same compelling value as it used to have earlier.

Further reading:

Thomas Blom Hansen, Wages of Violence:Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay, Princeton University Press, 2018

Steward Gordon, The Marathas, 1600-1818, Cambridge University Pres, 1998

Gail Omvedt, Cultural Revolt in a Colonial Society:The Non-Brahman Movement in Western India, Scientific Socialist Education Trust, 1976

S M Dahiwale, Consolidation of Maratha Dominance in Maharashtra, Economic and Political Weekly, 1995

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05