- India

- International

How citizenship was decided by makers of Indian Constitution

The formulation of citizenship in India’s Constitution was a meticulous process, fraught with debates and considerations. Influenced by colonial legacies and the aftermath of Partition, the framers crafted a unified citizenship framework that balanced inclusivity with safeguards against illegal migration.

The citizenship question plagued the farmers of the Indian Constitution for 2 years (Created by Abhishek Mishra)

The citizenship question plagued the farmers of the Indian Constitution for 2 years (Created by Abhishek Mishra)The members of the drafting committee of the Indian Constitution were well aware of the profound significance of being an Indian citizen, so much so that the controversy generated by the provisions on citizenship in the draft Constitution necessitated Jawaharlal Nehru to admit that the provisions had received far more thought and consideration than any in the Constitution.

The process, described by BR Ambedkar as a “headache” due to the two years it took to finalise, was complicated by the unprecedented consequences of the Partition, particularly the exodus it catalysed.

Pre-independence

In pre-colonial India, citizenship as it is understood in modern terms didn’t quite exist. Instead, society was organised into various hierarchical structures, with individuals’ rights and status often determined by factors such as caste, religion, occupation, and social standing.

During the colonial period, citizenship took on a more formalised character. Before getting into that, however, it is important to distinguish between two distinct phases of British rule. India was formally governed by the East India Company from 1757-1858. However, for much of the early 19th century, the Company had to share power with the British Crown. In 1858, the Crown formally took control, thereafter becoming the direct legal authority over British India. For 90 years, India would be ruled as a British colony until she achieved independence in 1947.

Historian Arun Sinha notes that these two phases of colonial rule were associated with two different conceptualisations of citizenship. He outlines the same in his 1958 article published in Sage Journals, Law of Citizenship and Aliens in India.

During the initial phase between 1757 and 1858, according to Sinha, there was no official citizenship law but instead Acts that granted rights to British subjects. However, as the Acts did not explicitly define the term ‘subject,’ there was uncertainty regarding whether they pertain solely to European British subjects or extended to the inhabitants of territories acquired from the Mughals. Consequently, there was ambiguity surrounding the status of native Indians and the extent of their rights and responsibilities.

During the second phase, from 1858 onward, India was divided into two primary political entities — British India, a larger portion directly governed by the British, comprising 54 per cent of the territory and 70 per cent of the population, further divided into provinces; and the princely states, encompassing about 565 distinct and widely dispersed units governed by local princes, kings, and feudal lords, with limited internal autonomy under British suzerainty.

By the end of this phase, there was a notable shift in the concept of British nationality. The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 replaced the common law understanding of nationality with a codified version, marking the first citizenship law in the British era. Additionally, the Act defined British subjecthood to include ‘natural born British subjects’ and individuals who obtained naturalization certificates from colonial authorities. Essentially, this created a two-tier system in which people born on the British mainland, or to British parents, were given higher status than native-born people in the colonies. Although both were assured protection by the British, particularly overseas, in application, those of Indian descent were relegated to second-class citizenship.

After Independence, India’s first Constituent Assembly was determined to change that.

Constitution

The Constitution of India came into effect on January 26, 1950. However, it’s worth noting that the sections regarding citizenship were only put into effect on the day of the Constitution’s adoption, which was November 29, 1949. These citizenship provisions applied to the entire country except for the State of Jammu and Kashmir. The Constitution introduced a unified form of citizenship, known as national citizenship, without the existence of separate citizenship based on states.

Although the term citizenship is not explicitly defined in the Constitution, Articles 5-11 outline the framework for citizenship at the time of the Constitution’s commencement. These provisions delineate the methods of acquiring citizenship, such as birth, domicile, and descent, as well as circumstances that disqualify individuals from obtaining Indian citizenship.

Article 5 specifically addresses citizenship at the outset of the Constitution. It establishes a dual requirement for granting citizenship, which includes being ‘domiciled’ in India and meeting one of three criteria — being born in Indian territory, having at least one parent born in Indian territory, or being a resident of Indian territory for a minimum of five consecutive years preceding the Constitution’s commencement.

The first day of the Constituent Assembly debates (Wikimedia Commons)

The first day of the Constituent Assembly debates (Wikimedia Commons)

The deliberations of the Constituent Assembly reveal that despite the discussions and acknowledgments of India’s illustrious history, the prevailing focus was on the imperative to construct a fresh society upon the remnants of the old. This motif of construction, of forging something novel, resonated in Nehru’s address on the eve of August 14, 1947, where he said, “We step out from the old to the new, when an age ends (and when) the future beckons to us.” The Constitution was crafted with the aim of materialising this innovative vision of India, propelling the nation towards the future while symbolically drawing a veil over the past.

One of the main challenges facing the framers was the very foundation of citizenship — whether it should be based on birth or descent.

The discussion primarily revolved around whether citizenship should be grounded in jus soli, whereby it is acquired by virtue of one’s birth on the nation’s soil, or jus sanguinis, which considers citizenship through descent or the nationality of one’s parents. The framers of India’s constitution ultimately opted for the jus soli principle, which Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel described as being emblematic of an “enlightened, modern, civilised” and democratic form of citizenship in contrast to jus sanguinis, criticised by Krishnaswami Ayyar as representing “an ideal of racial citizenship.”

P.S Deshmukh (Government of India Archives)

P.S Deshmukh (Government of India Archives)

However, some disagreed with the notion of allowing anyone born on Indian soil to be conferred with citizenship. Notable among the detractors was PS Deshmukh from Maharashtra who, during the Constituent Assembly Debates in 1949, argued that Ambedkar’s definition of citizenship would make “Indian citizenship the cheapest on earth.” His primary dissatisfaction was with the concept of citizenship by birth. He contended that if the proposed Article were to be approved, even a child born to a woman while she was passing through the Bombay port would be granted citizenship.

Citing the mistreatment of Indians abroad, Deshmukh further argued that, “In America, Indians can obtain citizenship at the rate of 116 or 118 per annum. That is the way in which other countries are safeguarding their own interests and restricting their citizenship.”

Deshmukh proposed that to obtain citizenship, a child must not only be born on Indian soil but also to Indian parents. This suggestion would eventually be adopted in 2003. More controversially, Deshmukh also called for all Hindus and Sikhs across the world to receive Indian citizenship, an idea that contradicted the secular leanings of Nehru, who had in 1929 and 1931, expressed a commitment to extending citizenship independent of religion.

Deshmukh defended his proposal, asking the Assembly, “Does it mean that we must wipe out our own people, that we must wipe them out in order to prove our secularity, that we must wipe out Hindus and Sikhs under the name of secularity.” Deshmukh was supported by Haryana representative Das Bhargava who argued, “Hindus and Sikhs have no other home but India…The phrase ‘secular’ should not frighten us in saying what is a fact and reality must be faced.”

It was during this moment that Nehru reportedly rose to express his discontent with the notion of “this secular-state business being thrown about.” He voiced his opinion that the Assembly should not perceive their commitment to secularism as an extraordinary act of generosity or sacrifice, emphasising, “We have only done something which every country does except a very few misguided and backward countries.”

Compounding these debates was the issue of Partition, which, by 1949, had gripped both India and Pakistan.

Partition

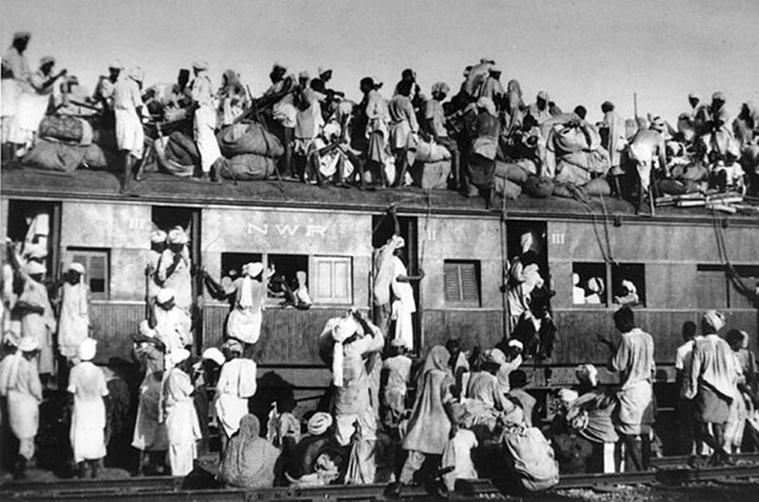

The Partition resulted in widespread displacement of people on either side of the border. From Independence in 1947 until the Constituent Assembly adopted the Constitution of India on 26 November 1949, there was a gap in Indian citizenship law. This gap left the status of individuals as Indian citizens uncertain during a period of immense humanitarian crisis and national identity turmoil.

The Indian stance on people who relocated from Pakistan to India post-Independence marked a pivotal moment where citizenship began to adopt religious undertones. Initially, unrestricted travel between the dominions was advocated, considering both as a unified economic entity.

However, economic realities prompted a shift in policy. From March 1948, the Constituent Assembly of India grappled with issues concerning the rights and citizenship of returning minorities. Pakistan’s alleged refusal to return property to returnees in West Pakistan was contrasted with India’s eagerness to restore property to those returning to India.

Following Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination and Pakistan’s initial economic challenges, Muslims began returning to regions like UP, Rajputana, and Delhi. As the influx continued into the summer of 1948, concerns grew about the emergence of ‘miniature Pakistans’ within Indian territory, according to Kapur. Even involuntary migration during communal unrest, facilitated by military escorts, was viewed as disloyalty to the fledgling dominion.

During the Constituent Assembly Debates, Jaspat Roy Kapoor, hailing from the United Provinces, voiced the viewpoint that individuals who had chosen to align themselves with Pakistan should not be permitted to return. He stated that “once an individual has migrated to Pakistan and shifted their allegiance from India to Pakistan, their migration is finalised.”

On the other end of the spectrum was Brajeshwar Prasad from Bihar who argued that many people who went to Pakistan had “fled in panic,” even going as far as to propose blanket citizenship for all Pakistanis. He said, “I wish all the people of Pakistan should be invited to come and stay in this country if they so like….I see no reason why a Muslim who is a citizen of this country should be deprived of his citizenship at the commencement of this constitution, (e)specially when we are inviting Hindus who have come to India from Pakistan to become citizens of this country.”

At the time these discussions were taking place, an ordinance was already in effect, terminating the free movement between India and West Pakistan. According to a temporary Act passed in July 1948, all movement from West Pakistan to India required one of five kinds of permits provided by the Indian Government.

As highlighted by Assembly members, Indian authorities were obligated to grant these permits very selectively. Notably, East Pakistan, which housed a significant minority population, was excluded from the permit system, and the border remained unrestricted until shortly before the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war.

Overcrowded train transferring refugees during the partition of India, 1947. (Wikimedia Commons)

Overcrowded train transferring refugees during the partition of India, 1947. (Wikimedia Commons)

However, the ultimate citizenship provisions indirectly delineated the lines drawn by the Partition. In simple terms, during the citizenship debates, Ambedkar recognised that the rules being created for citizenship had two main ideas. One was to be very welcoming and open to everyone, which is called liberal. The other idea was more about prioritising certain groups of people based on their ethnicity, which is called ethnonationalism. Ambedkar wanted to balance these two ideas. So, he suggested making rules that would let most people become citizens, but also included rules to control who could come into the country during the chaotic time when India and Pakistan were being formed after Partition. He acknowledged that the developing articles on citizenship encompassed both a liberal understanding of citizenship and an ethnonationalism concept.

As Ambedkar outlined to the Assembly, “persons coming from Pakistan to India in the matter of their acquisition of citizenship on the date of the commencement of the Constitution are put into two categories— those who have come before July 19, 1948, and those who have come afterward. In the case of those who have come before July 19, 1948 citizenship is automatic. No conditions, no procedure is laid down with regard to them. With regard to those who have come thereafter, certain procedural conditions are laid down and when those conditions are satisfied, they also will become entitled to citizenship under the article we now proposed.”

The permit system proved controversial however, with Mahboob Ali Baig Sahib of Madras arguing that “you have stated that if a person is born in India as defined in the 1935 Act he is a citizen of India. Why do you want a certificate from him when he returns to India?”

Addressing the logic behind the permits (that people coming back would be disloyal to India,) he said, “What would you do if one of your men becomes a traitor, a Communist and tries to overthrow the Government? So, to say those people coming to India might become traitors and therefore they should not be allowed to come back, that is no reason at all.”

Nehru, for his part, defended the system, saying that it did not discriminate against any religious group. That being said, he also acknowledged that the system would initially favour Hindus and Sikhs. Despite Nehru’s assertions, the permit system did disproportionately affect Muslims. As Manav Kapur, a legal scholar, points out in a 2021 article India’s Citizenship Amendment Act for the Statelessness and Citizenship Review, “case law on citizenship and migration through the first 20 years of India’s Independence show subtle and not-so-subtle biases against Muslims.”

Post-independence

In Citizenship and its Discontents, political scientist Niraja Jayal makes a compelling argument tracing the evolving nature of Indian citizenship, shifting from the principle of jus soli to jus sanguinis. Initially, Jayal says, at the dawn of the Constitution, citizenship rights were primarily determined by jus soli, where birth on Indian soil conferred citizenship, albeit intertwined with other criteria. However, in recent times, Jayal suggests that Indian citizenship has increasingly leaned towards jus sanguinis, emphasising descent or parental citizenship, while explicitly disfavouring Muslims.

The constitutional provisions were initially intended to define citizenship at the Constitution’s commencement. While the Constitution addressed citizenship at its outset, the Citizenship Act of 1955 aimed to delineate the substantive aspects of citizenship thereafter.

Section 3 of the Citizenship Act, 1955 stipulated that “every person born in India on or after January 26, 1950 shall be a citizen of India by birth.” However, after 1986, an additional condition required at least one parent to be an Indian citizen at the time of the child’s birth for the child to inherit Indian citizenship.

In 2003, the criteria for Indian citizenship underwent a tightening. To qualify as an Indian citizen, an individual had to be born in India with both parents being Indian citizens, or one parent being an Indian citizen while the other could not be an illegal migrant at the time of birth. This amendment aimed to make the acquisition of Indian citizenship through registration and naturalisation more rigorous and prevent illegal migrants from obtaining Indian citizenship.

The concern regarding illegal migration traces back to the Constituent Assembly and debates surrounding the status of Assam. As Pandit Thakur Das Bhargava, from East Pakistan, said at the time, “After the Partition for reasons best known to themselves many Musalmans have come to Assam with a view to make a Muslim majority in that province for election purposes and not to live in Assam as citizens of India.”

The birth of Bangladesh in 1971 compounded the issue, introducing the Bangladeshi dimension to the foreigners’ crisis. By the late 1970s, the presence of foreigners on electoral rolls emerged as a significant issue in Assam politics. Against the backdrop of mass migration from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, the amendments in the Citizenship Act and the 2003 revisions were enacted.

Further Reading

Law of Citizenship and Aliens in India, A.N Sinha, Sage Publications, 1958

India’s Citizenship (Amendment) Act, Manav Kapur, Princeton University, 2021

Citizenship and Minorities in the Constituent Assembly Debates: Making Sense of the Present, Paramjit S. Judge, Sage Publications, 2022

Constituent Assembly Debate relating to 6th Schedule (excerpts), Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council

Citizenship and its Discontents, Niraja Jayal, Harvard University Press, 2013

Apr 05: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05