- India

- International

Why Uttarakhand govt wants to evaluate the risk of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods

Rising temperatures have increased the risk of glacial lake bursts of the kind that devastated the Kedarnath valley in 2013 and parts of Chamoli in 2021.

Rising surface temperatures across the globe, including India, have increased the risk of GLOFs. Studies have shown that around 15 million people face the risk of sudden and deadly flooding from glacial lakes, which are expanding and rising in numbers due to global warming. (Representational/file photo)

Rising surface temperatures across the globe, including India, have increased the risk of GLOFs. Studies have shown that around 15 million people face the risk of sudden and deadly flooding from glacial lakes, which are expanding and rising in numbers due to global warming. (Representational/file photo)

The Uttarakhand government has constituted two teams of experts to evaluate the risk posed by five potentially hazardous glacial lakes in the region. These lakes are prone to Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs), the kind of events that have resulted in several disasters in the Himalayan states in recent years.

The goal of the risk assessment exercise is to minimise the possibility of a GLOF incident and provide more time for relief and evacuation in case of a breach.

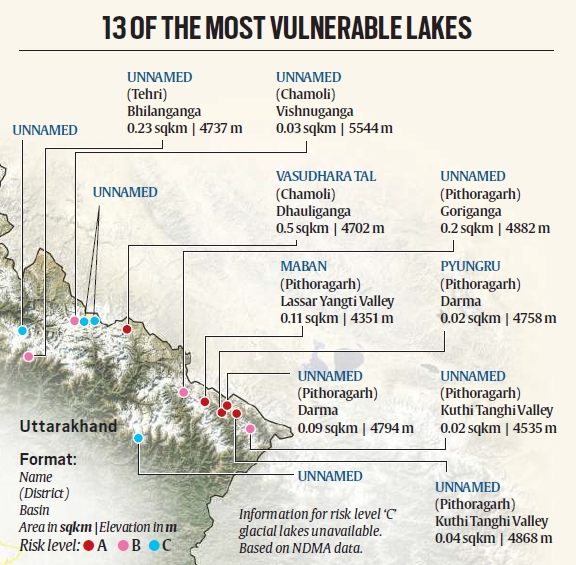

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), which operates under the Union Ministry of Home Affairs, has identified 188 glacial lakes in the Himalayan states that can potentially be breached because of heavy rainfall. Thirteen of them are in Uttarakhand.

Lakes in Uttarakhand’s Pithoragarh and Chamoli districts are more vulnerable to flooding.

Lakes in Uttarakhand’s Pithoragarh and Chamoli districts are more vulnerable to flooding.

Rising surface temperatures across the globe, including India, have increased the risk of GLOFs. Studies have shown that around 15 million people face the risk of sudden and deadly flooding from glacial lakes, which are expanding and rising in numbers due to global warming.

What are GLOFs?

GLOFs are disaster events caused by the abrupt discharge of water from glacial lakes — large bodies of water that sit in front of, on top of, or beneath a melting glacier. As a glacier withdraws, it leaves behind a depression that gets filled with meltwater, thereby forming a lake.

The more the glacier recedes, the bigger and more dangerous the lake becomes. Such lakes are mostly dammed by unstable ice or sediment composed of loose rock and debris. In case the boundary around them breaks, huge amounts of water rush down the side of the mountains, which could cause flooding in the downstream areas — this is referred to as a GLOF event.

GLOFs can be triggered by various reasons, including glacial calving, where sizable ice chunks detach from the glacier into the lake, inducing sudden water displacement. Incidents such as avalanches or landslides can also impact the stability of the boundary around a glacial lake, leading to its failure, and the rapid discharge of water.

GLOFs can unleash large volumes of water, sediment, and debris downstream with formidable force and velocity. The floodwaters can submerge valleys, obliterate infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and buildings, and result in significant loss of life and livelihoods.

Why are GLOFs under the spotlight?

In recent years, there has been a rise in GLOF events in the Himalayan region as soaring global temperatures have increased glacier melting. Rapid infrastructure development in vulnerable areas has also contributed to the spike in such incidents.

Since 1980, in the Himalayan region, particularly in southeastern Tibet and the China-Nepal border area, GLOFs have become more frequent, according to a study, ‘Enhanced Glacial Lake Activity Threatens Numerous Communities and Infrastructure in the Third Pole’, published in the journal Nature in 2023. The analysis was done by Taigang Zhang, Weicai Wang, Baosheng An and Lele Wei — all from the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research in China.

“Approximately 6,353 sq km of land could be at risk from potential GLOFs, posing threats to 55,808 buildings, 105 hydropower projects, 194 sq km of farmland, 5,005 km of roads, and 4,038 bridges in the region,” according to the study.

Another analysis, ‘Glacial Lake Outburst Floods Threaten Millions Globally’, published in the journal Nature in February 2023, showed that about 3 million people in India and 2 million in Pakistan face the risk of GLOFs. This study was conducted by Caroline Taylor, Rachel Carr and Stuart Dunning of Newcastle University, the United Kingdom, Tom Robinson of the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, and Matthew Westoby of Northumbria University, the UK.

“While the number and size of glacial lakes in these areas (India and Pakistan) isn’t as large as in places like the Pacific Northwest or Tibet, it’s that extremely large population and the fact that they are highly vulnerable that mean Pakistan and India have some of the highest GLOF danger globally,” Tom Robinson, co-author of the study and lecturer in Disaster Risk & Resilience at the University of Canterbury, told The Indian Express in February last year.

What is the situation in Uttarakhand?

Uttarakhand has witnessed two major GLOF events in the past few years. The first took place in June 2013, which affected large parts of the state — Kedarnath valley was the worst hit, where thousands of people died. The second occurred in February 2021, when Chamoli district was hit by flash floods due to the bursting of a glacier lake.

As mentioned earlier, Uttarakhand has 13 glacial lakes which are prone to GLOF. Based on the analysis of available data and research from various technical institutions, these lakes have been categorised into three risk levels: ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’.

Five highly sensitive glacial lakes fall into the ‘A’ category. These include Vasudhara Tal in the Dhauliganga basin in Chamoli district, and four lakes in Pithoragarh district — Maban Lake in Lassar Yangti Valley, Pyungru Lake in the Darma basin, an unclassified lake in the Darma basin, and another unclassified lake in Kuthi Yangti Valley.

The areas of these five lakes range between 0.02 to 0.50 sq km, and they are situated at elevations ranging from 4,351 metres to 4,868 metres.

The rising surface temperatures could worsen the situation in Uttarakhand. The state’s annual average maximum temperature may increase by 1.6-1.9 degree Celsius between 2021-2050, according to a 2021 study, ‘Locked Houses, Fallow Lands: Climate Change and Migration in Uttarakhand, India’, carried out by the Germany-based Potsdam Institute for Climate Research (PIK) and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) in New Delhi. This could exacerbate the risk of GLOFs in the state.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 04: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05